Tales lull our childhood and trace our history

We’ve all read or heard enchanting tales from fairy tale books—stories that make us dream, tremble, laugh, or reflect. But have you ever wondered where these stories come from? To answer this question, I invite you on a journey through the history of storytelling. Along the way, we’ll see that stories are not only deeply personal, but also woven into the fabric of our shared human history.

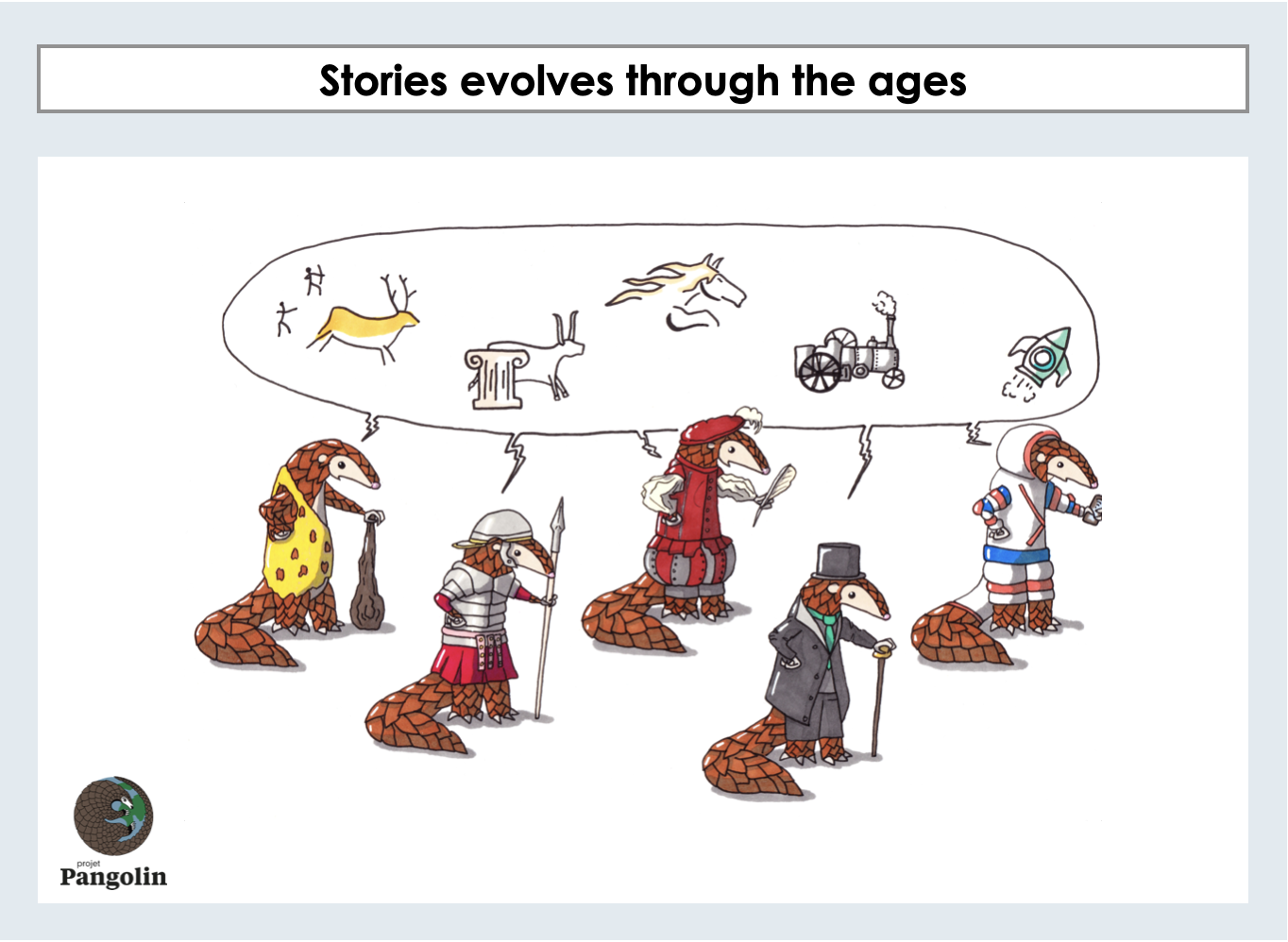

We’ll begin by exploring the reasons why humans have always created stories—and why we continue to do so. We’ll discover that storytelling is a universal trait: every culture has its tales, which evolve and adapt through the ages.

Next, we’ll examine how science—particularly phylogenetics (don’t worry, we’ll explain what that means!)—can be applied to trace the evolution of stories, much like we trace the lineage of living species.

Finally, we’ll dive into the rich imaginations of our ancestors by analyzing two stories with particularly intriguing and unusual origins.

Now, let’s embark on this fascinating journey together!

Why do humans tell stories?

Humans have been telling stories for tens of thousands of years—long before writing existed. Like language, stories are a form of information passed down from generation to generation. Through storytelling, we share experiences, convey ideas, and transmit values that help shape how we understand ourselves, our history, and the world around us. But have these stories remained the same over time, or have they evolved with us through the ages?

Have these stories evolved over the centuries?

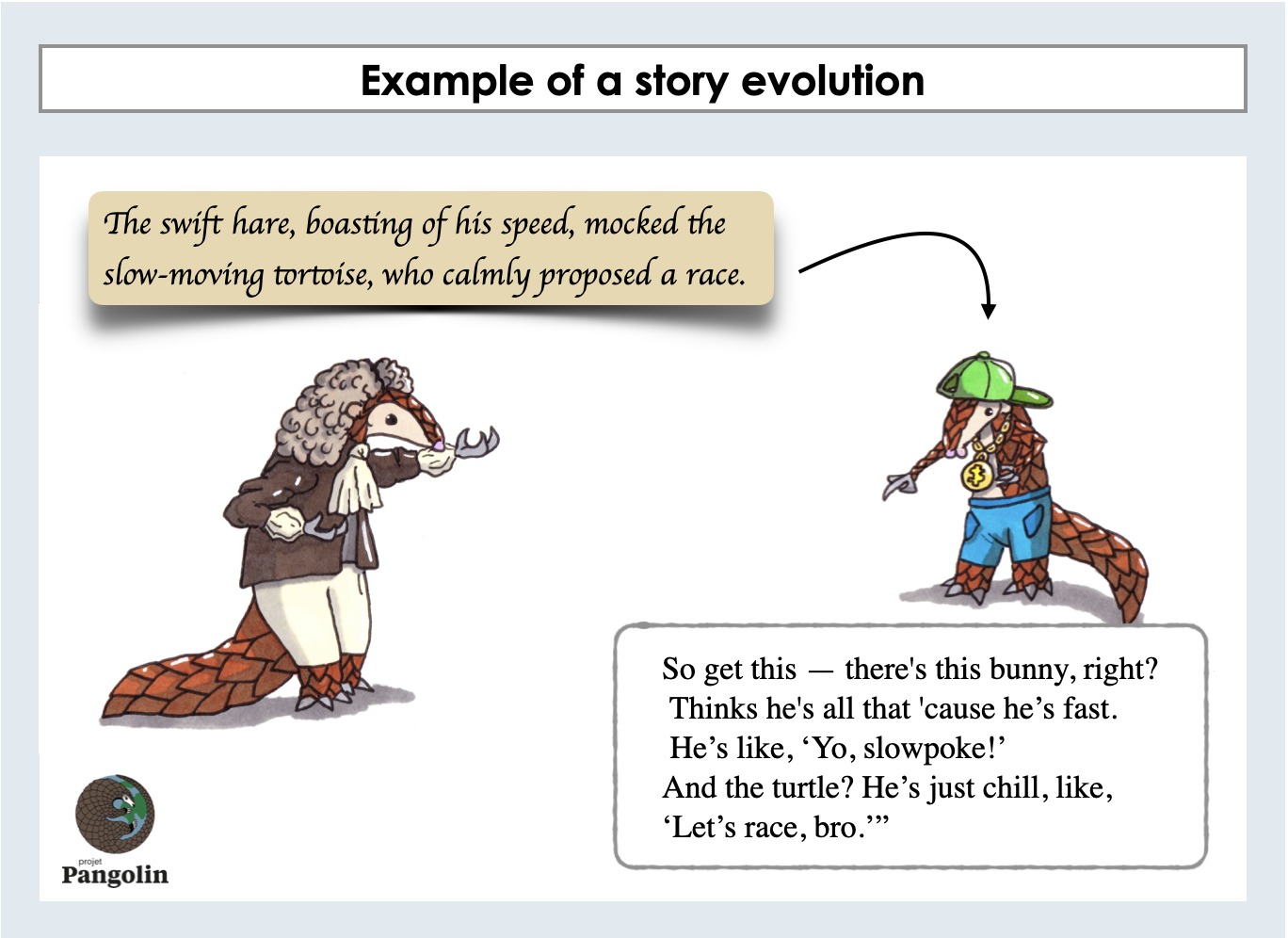

Versions of a story often reflect specific moral standards and mores close to the social classes that tell them. So it’s not unusual to see adaptations that meet the needs of their audience [1].

Modern stories, though imprinted in the memories of countless storytellers, have been completely transformed from their original versions. Over time, these stories have been imbued with the various desires, struggles and complaints of their tellers, and provide perfect snapshots of the societies that created or modified them.

Let’s take a very famous example. Jean de la Fontaine wrote a fable called ‘The Court of the Lion’, which is a story inspired by another fable called ‘The Reigning King’ written by Phaedra. Jean de la Fontaine modified the story to make it rhyme and, above all, to reflect the reality of Louis XIV’s court.

Is storytelling universal?

Across centuries and continents, stories have always been tied to specific times and cultures [2]. Think of biblical tales like Noah’s Ark, Greek myths such as Narcissus, or even more recent legends like Slenderman, which emerged on the internet in the early 2000s. Many stories are closely associated with particular cultural origins—for example, Peter and the Wolf in Russian folklore, Hansel and Gretel in German tradition, Le Petit Poucet (Little Thumb) in French tales, and Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves from Persian and Arabic lore.

What’s particularly intriguing is that when you leaf through the pages of the famous Grimm brothers’ collection [3], you start to notice striking similarities between some of these tales. Take Little Red Riding Hood, for instance—a story that appears in surprisingly similar forms across many different cultures. (Stay with us—we’ll dive deeper into this fascinating example a bit later!)

Using biology to solve folklore problems

A question then arises in folkloristics (the study of popular traditions and customs): where do these stories come from?

To explore the origins and evolution of stories, we must rely on the traces that have withstood the passage of time. Yet most of these tales have been passed down orally, leaving behind few written records—much like the sparse fossil evidence available to paleontologists. This makes tracing the history of stories particularly challenging, even with the tools of traditional literary analysis.

To overcome these limitations, a promising new approach in folkloristics has emerged: the application of mathematical methods borrowed from biology to study the evolution of storytelling [4–6]. Just as biologists reconstruct the evolutionary trees of living species, researchers can now use similar tools to map the branching paths of narrative traditions across cultures and time.

But how does it work?

To better understand how these mathematical tools work, let’s first draw a parallel with the evolution of species and how scientists reconstruct their history.

The theory of evolution—which explains the incredible diversity of life on Earth—was developed in the mid-19th century by biologists such as Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace [7]. In simple terms (see our article on the topic for more details), evolution describes how organisms change over time through genetic variation. These changes can affect an organism’s physical traits or behavior. If a particular change proves beneficial, it is more likely to be passed down to future generations. This foundational theory—and the scientific advances that followed—transformed how we understand the living world.

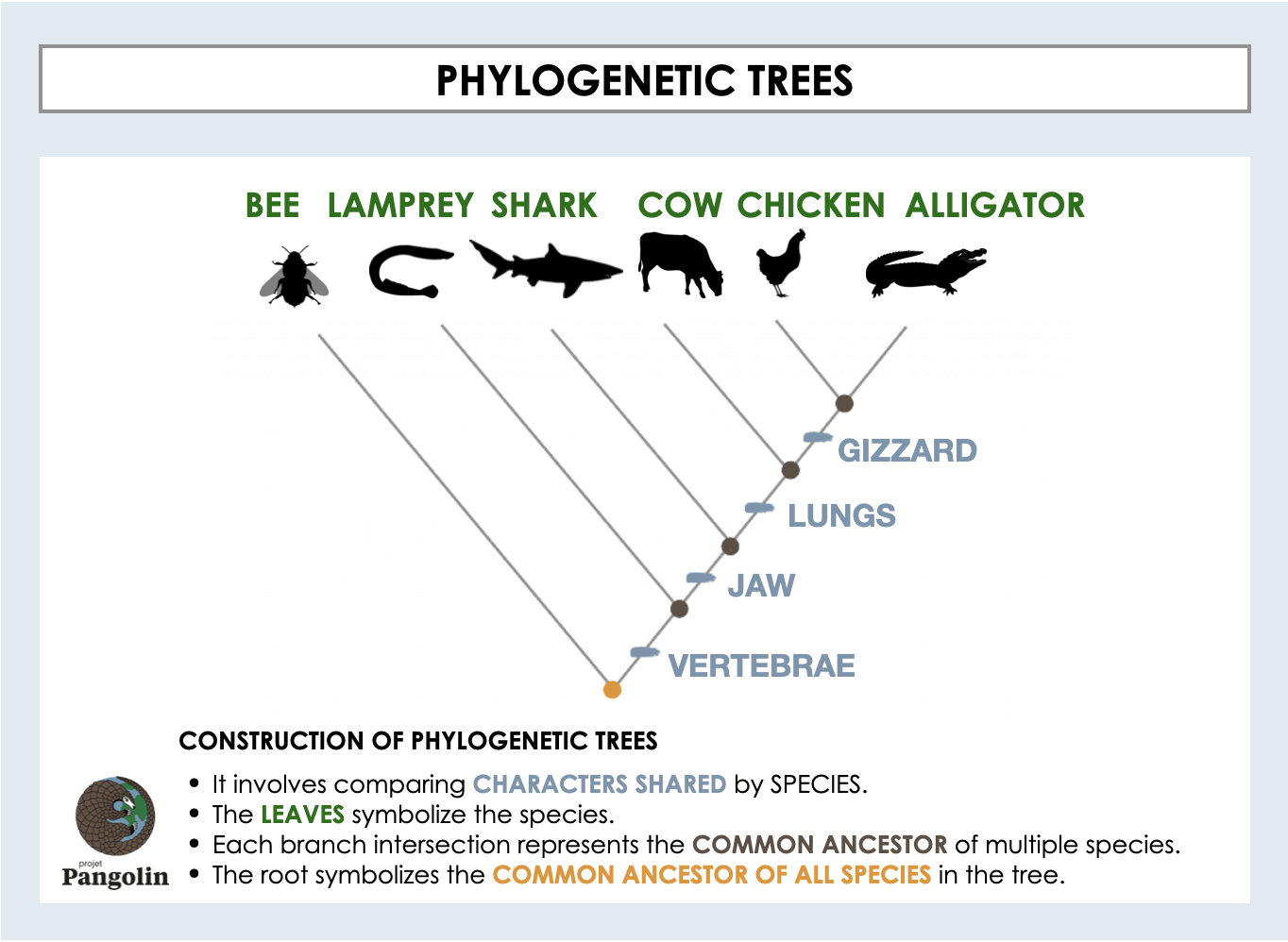

One powerful tool that emerged from this theory is phylogeny: the study of the evolutionary relationships among organisms.

Wait—“phylogeny”? That might sound like an intimidating word, but it’s not so scary once you break it down. It comes from the Greek phylon, meaning “tribe” or “species”, and gennan, meaning “to produce” or “to generate”. So, phylogeny quite literally means the study of the formation of species. In practice, it helps scientists trace how living organisms have evolved over time and how they are related to one another.

The link between phylogeny and fairytales

ou might be wondering—what does phylogeny have to do with stories? As the renowned anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss once observed [8], stories, much like living organisms, likely evolve through the gradual accumulation of inherited traits. Just as species change over time, the earliest versions of stories adapt, mutate, and diversify as they are passed from one generation to the next. As they spread across cultures and environments, these tales evolve—sometimes subtly, sometimes dramatically—giving rise to distinct local variations.

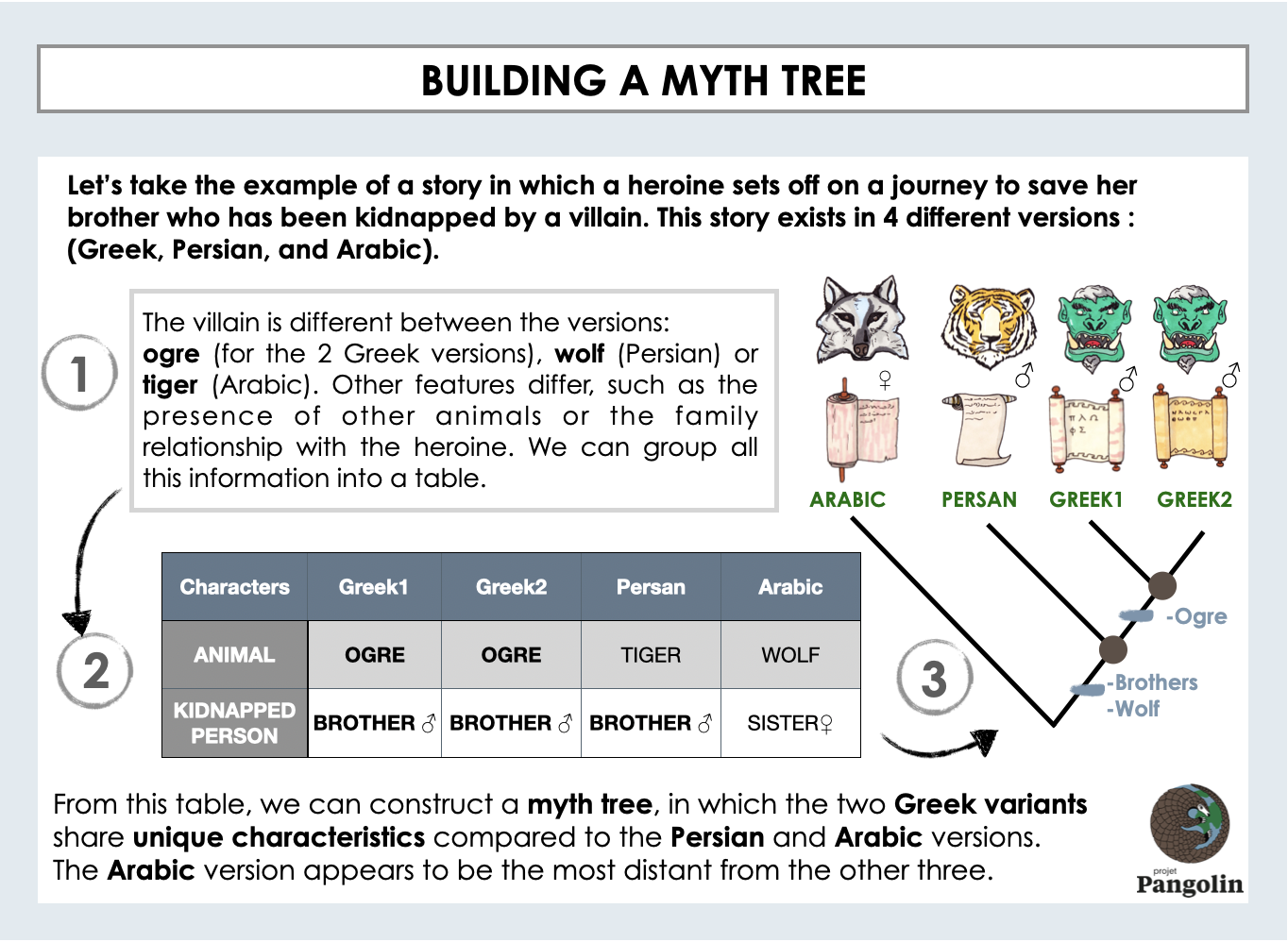

To study how stories differ across cultures and historical periods, researchers identify a set of defining features, or “mythemes,” which they can compare across story variants.

These features might include the gender of the protagonist (girl or boy), the nature of the antagonist (wolf, tiger, ogre), or the setting of the tale (forest, village, mountain). By analyzing these elements, we can trace how stories transform and branch out—just like species on an evolutionary tree.

The idea is to analyse these characteristics as if they were physical characteristics or genes and to use them to reconstruct the genealogy of the story, just as we would for a species phylogeny. So, if two histories have similar characteristics, it is likely that they have a recent common origin.

Little Red Riding Hood

Little Red Riding Hood is one of the world’s most popular tales. This tale delicately explores our greatest fears. It’s a story about the struggle between good and evil, about greed and hope, about responsibility and second chances.

The classic tale

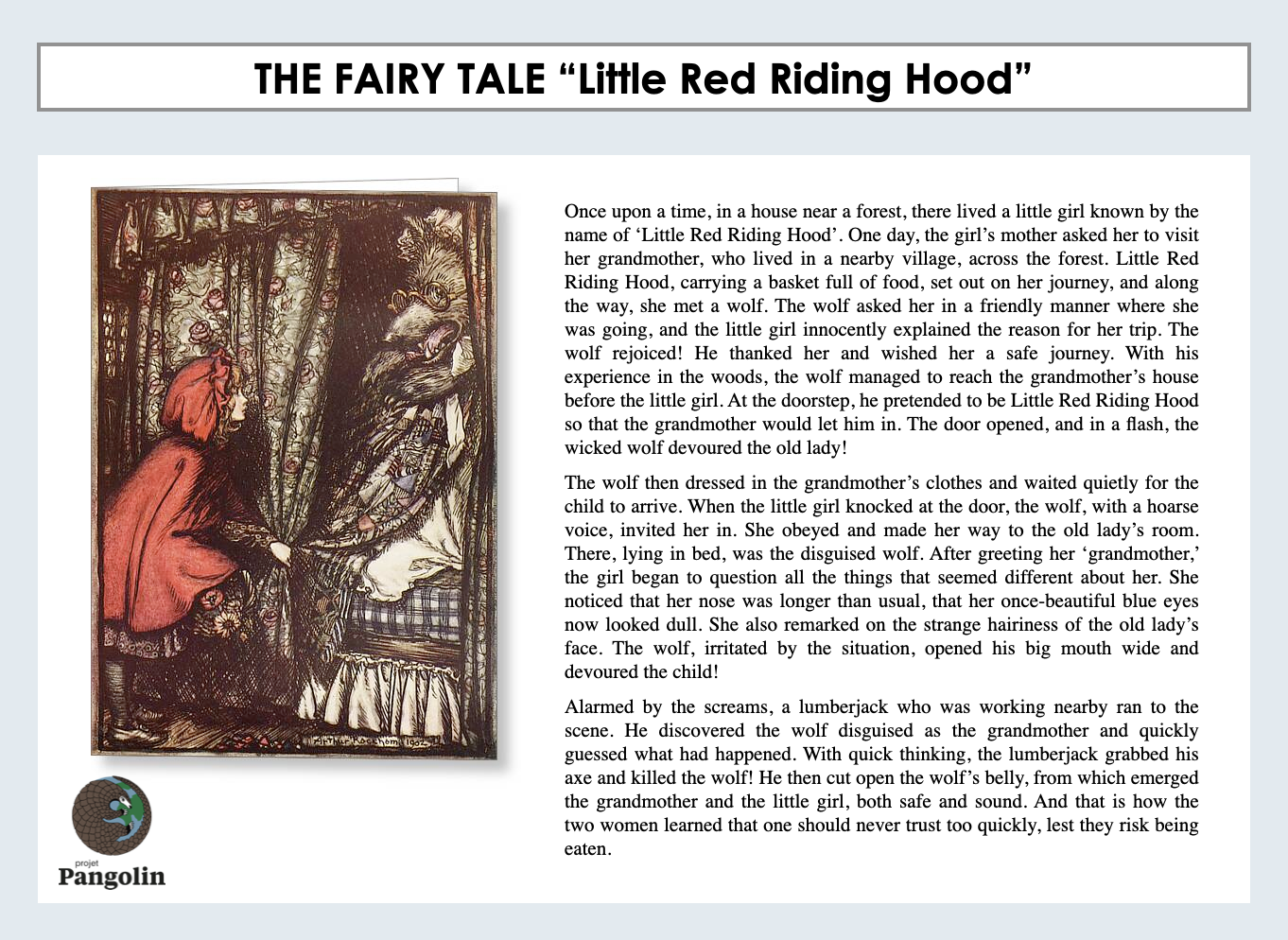

If this story sounds familiar, it’s because you’ve likely inherited the French version of Little Red Riding Hood, first written by Charles Perrault in the late 17th century [9,10] and later popularized by the Grimm brothers in their famous collection [3].

But if you’re raising an eyebrow and thinking, “Wait, that’s not how I remember it,” you’re not alone—and you’re absolutely right. There are many different versions of this tale from around the world! In some, there’s no heroic hunter at all, and the girl cleverly escapes by pretending she needs to go outside for a call of nature. In others, the iconic red hood is completely absent. Each version carries its own twist, shaped by the culture and time in which it was told.

Strangely similar tales

Striking similarities to Little Red Riding Hood, don’t you think?

What’s even more intriguing is that tales with nearly identical structures and themes can be found in many parts of the world—including across Africa and East Asia [10–11]. This raises a fascinating question: could all these stories share a common origin?

Now, what if I told you that to explore this question, we can actually turn to the biological methods we discussed earlier? Surprising, isn’t it?

Little Red Riding Hood: an old story

Even before scientific studies entered the picture, anthropologists were captivated by the parallels between Little Red Riding Hood and The Wolf and the Seven Young Goats. The similarities were so pronounced that researchers long debated whether these stories stemmed from a shared ancestral tale or had developed independently. The question remained open—until new methods offered a fresh perspective.

To unravel these questions, one researcher conducted a phylogenetic study of the Little Red Riding Hood story. He examined 58 versions of the tale and identified no fewer than 72 distinct plot variants [12]! And to trace their origins, there was only one option: read them all. As you can imagine, collecting such a vast dataset is no small task. It often involves making choices—some more debatable than others [13]. Still, this pioneering study opened the door for future folklorists to take a more rigorous and systematic approach.

Geographical Origins

The results revealed that both Little Red Riding Hood and The Wolf and the Seven Young Goats originated in Europe. Traces of Little Red Riding Hood can be found as early as the Middle Ages [14]. However, the two stories differ enough in structure and content to be considered separate tales with distinct origins.

Variants found in Africa appear to be adapted versions of The Wolf and the Seven Young Goats. Researchers believe this tale was introduced through trade or colonial contact, later evolving into a localized version that spread throughout central and southern Africa—even reaching the Caribbean islands.

In contrast, the Asian tale The Tiger and the Grandmother seems to be a fascinating hybrid, blending elements from both Little Red Riding Hood and The Wolf and the Seven Young Goats. Yet its exact origins remain something of a mystery.

Fascinating, isn’t it?

And if you’re still not convinced of the power of phylogenetic tools to study the evolution of fairy tales, don’t worry—we have one more captivating example coming up.

The Cosmic hunt in the Berber sky

15,000 years ago…

Let’s continue with a much older story.

In the Palaeolithic era, when our ancestors still lived as hunter-gatherers, the world as we know it today didn’t exist. The cap wasn’t invented until the early 19th century, the crown dates back to Antiquity, and even the object we now call a saucepan is a relatively recent innovation. Humans of that time had a completely different relationship with their environment—one that was far more attuned to nature. But how can we possibly glimpse what they imagined?

What if I told you that, once again, phylogenetic methods offer a way to infer the contents of our ancestors’ imaginations? You’d be right to be sceptical—but the approach is genuinely intriguing and deserves a closer look.

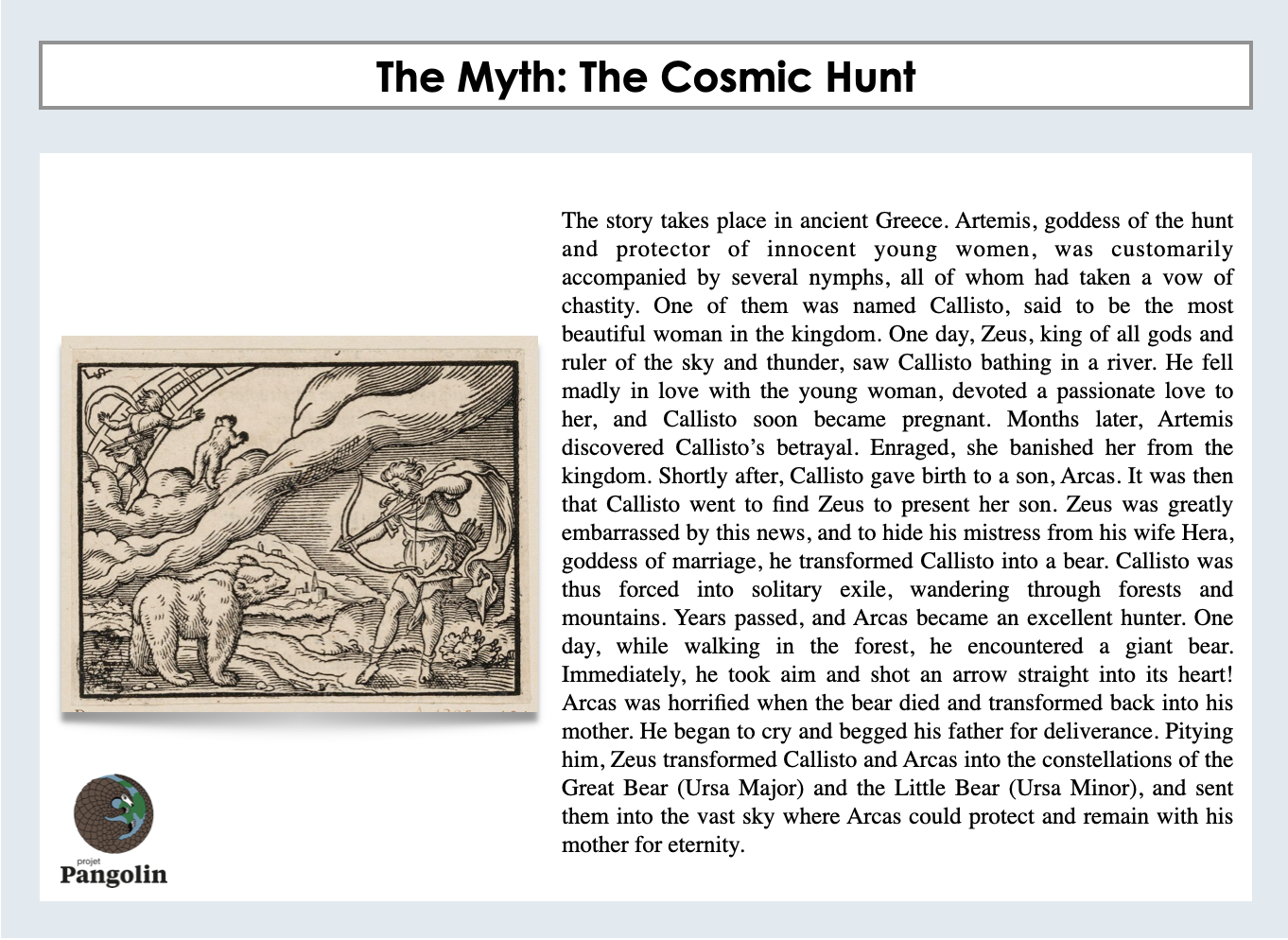

The Myth

It all begins with a tale found across continents—in Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Americas [15]: the Cosmic Hunt. While the characters and constellations vary, all versions share a central narrative thread: a man pursues or kills one or more animals, and these animals are ultimately transformed into stars.

Versions of the Cosmic Hunt can be found all over the world. Take, for example, the tale of the Iroquois peoples of North America. In their story, three hunters chase a bear whose blood stains the autumn leaves as it flees. The bear climbs a mountain and leaps into the sky, transforming along with the hunters into the constellation of the Big Dipper. Meanwhile, among the Chukchi of Siberia, the constellation Orion represents a hunter pursuing a reindeer, while Cassiopeia plays a key role in their celestial stories.

How can we explain these striking similarities across such distant cultures? One possible explanation is the convergence hypothesis—that these myths arose independently in separate regions due to similar human experiences or a shared collective subconscious. In other words, different peoples might have crafted similar stories because certain symbols and themes resonate universally when trying to make sense of the world.

However, this theory isn’t the most convincing one, especially in light of the research conducted by a researcher who offers a different perspective.

The phylogenetic study

In this study, the researcher analyzed 47 versions of the story and identified 93 distinct variants [15]. Interestingly, these versions are rarely found in Australia and virtually absent from Indonesia and New Guinea. In contrast, many versions appear on both sides of the Bering Strait—the stretch of water that once connected Eastern Siberia and Alaska about 20,000 years ago, when it was above sea level [16,17]. Taken together with phylogenetic reconstructions, these findings suggest that the story has a very ancient origin, tracing back to the common ancestors of Berber populations and European hunter-gatherers.

Data on human migrations further support this hypothesis. As our ancestors migrated from Eurasia into the Americas—crossing the Bering land bridge before it was submerged under rising seas—they likely carried this story with them. The presence of the tale in Africa also aligns with the well-established theory that humans later migrated back from Eurasia into the African continent.

The researcher even attempted to reconstruct the original version of the myth, imagining what our ancestors might have envisioned more than 15,000 years ago. Here is the proposed narrative: “A large herbivore, probably an elk, is chased by a hunter. To escape, the elk gallops up into the sky, where it transforms in a burst of light into a cluster of stars—the constellation we now call the Big Dipper.”

Of course, this reconstruction is only an approximation. Still, it offers a fascinating glimpse into the imagination of our distant ancestors and invites us to envision how these ancient stories might have taken shape.

This is just one example, but many others can be found in the literature—for instance, the tale of The Smith and the Devil, which was adapted into a Netflix film in the Basque language, can be traced back to the Bronze Age [18].

Conclusion, between tales and stories

It is truly remarkable that these stories have survived for millennia without ever being written down. They were passed along long before our modern languages existed, spoken in dialects now lost to time. Yet, through the enduring power of storytelling, these tales have persevered. Their motifs are timeless and universal—exploring fundamental dichotomies such as good versus evil, love versus hate, and moral versus immoral. Though often dismissed as mere fiction or children’s narratives, folk tales continue to nourish and enrich our collective imagination.

Final word

Over the centuries, the ways we tell stories have evolved dramatically. In humanity’s earliest days, our ancestors likely gathered around a fire, weaving tales born from their natural surroundings and vivid imaginations. Today, stories are shared instantly with a click. We are privileged to have access to this vast legacy of storytelling—and we should cherish it. But more importantly, we must keep sharing these stories and let them inspire us to create new ones. Because if there is one thing humanity can truly be proud of, it is the boundless power of our imagination.

Illustrations: Vincent Lhuillier Reviewing: The Project Pangolin team

References

-

Encyclopedia.com., 2020. Evolution Of Fairy Tales Encyclopedia.Com. - Hughes, H., 1998. Storytelling Encyclopedia:98252David Adams Leeming, Marion Sader Edited by. Storytelling Encyclopedia: Historical, Cultural, and Multiethnic Approaches to Oral Traditions Around the World. Phoenix, Az. and London

- Grimm J, Grimm W., 1812. Children’s and Household Tales. Gottingen.

- Julien d’Huy et Jean-Loïc Le Quellec., 2004. « Comment reconstruire la préhistoire des mythes ? Applications d’outils phylogénétiques à une tradition orale »

- Korotayev, D, Khaltourina., 2011. Myths and Genes: a Deep Historical Reconstruction. Moscow: Librokom/URSS (ISBN 978–5–397–01175–4)

- Thuillard, M., Le Quellec, J., d’Huy, J. and Berezkin, Y., 2018. A Large-Scale Dtudy of World. Trames. Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 22(4), p.407.

- Darwin, C. R. & A. R. Wallace., 1858. Proceedings of the meeting of the Linnean Society held on July 1st, 1858. Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society. Zoology 3: liv-lvi.

- Lévi-Strauss Claude., 1971. Mythologique4. L’Homme nu. Paris, Plon, 681p.

- Perrault C.,1697. Histoires ou Contes du temps passe´. Hood’’. Speculum 67: 549–575

- Frazer JG., 1889. A South African Red Riding-Hood. The Folk-Lore Journal 7:

- Ikeda H., 1971. A Type and Motif Index of Japanese Folk Literature. Helsinki: FF Communications

- Jamshid J. Tehrani., 2013. The Phylogeny of Little Red Riding Hood, PLOS ONE, vol. 8, n°11: e78871.

- Patrice Lajoye, Julien d’Huy and Jean-Loïc Le Quellec., 2013. reply to tethrani ; http://nouvellemythologiecomparee.hautetfort.com

- Ziolkowski JM., 1992. A fairy tale from before fairy tales: Egbert of Liege’s ‘‘De puella a lupellis seruata’’ and the medieval background of ‘‘Little Red Riding

- Julien d’Huy. A Cosmic Hunt in the Berber sky: : a phylogenetic reconstruction of a Palaeolithic mythology.. Les Cahiers de l’AARS, 2013, 15, pp.93-106. halshs-00932197

- Bond, J.D., 2019. Paleodrainage map of Beringia. Yukon Geological Survey,

- Geggel, L., 2019. Humans Crossed The Bering Land Bridge To People The Americas. Here’S What It Looked Like 18,000 Years Ago.. [online] livescience.com.

- Da Silva, S. and Tehrani, J., 2016. Comparative phylogenetic analyses uncover the ancient roots of Indo-European folktales. Royal Society Open Science, 3(1), p.150645.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: