Natural Selection

Has your mind ever been stirred by the sight of an eagle swooping down on its prey, or a giraffe whose remarkably long neck seems perfectly suited to the height of the trees? If so, you’ve already begun to wonder how such wonders of nature came to be. Part of the answer lies in the powerful concept of natural selection.

To explore this idea together, I invite you to embark on a journey:

-

First, we’ll travel back in time to revisit the early thoughts of our ancestors.

-

Then, we’ll dive into the heart of the matter and unravel the mechanisms behind the theory known as natural selection.

-

We’ll see how chance, guided by nature, can endow certain species with astonishing abilities.

-

And to fully convince you, we’ll examine a striking example of evolution that unfolds within a single human lifetime.

Finally, we’ll take a look at some of the key controversies that have shaped the history of this groundbreaking theory.

So, what exactly is evolution?

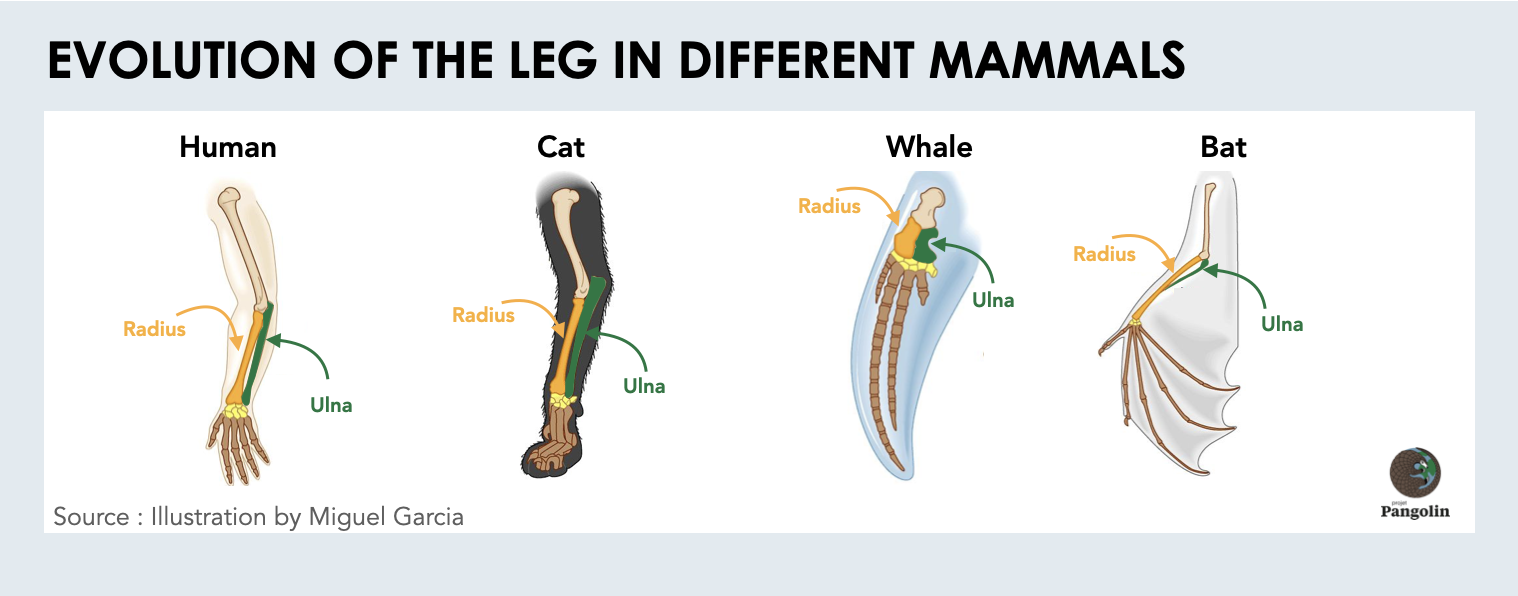

In biology, evolution refers to the change in characteristics of a given species over multiple generations — such as the shape of a bird’s beak or the development of limbs in tetrapods. This process is driven by several evolutionary mechanisms.

Among these, natural selection is undoubtedly the most well-known and extensively studied by scientists — and it’s precisely this concept that we’ll explore in this article.

The Story of a Theory: Natural Selection

I hope you’ll forgive me for not recounting the entire history of natural selection here! Instead, I’ll focus on some of the key milestones along the way. 🙂

Like all scientific disciplines, evolutionary biology has its own philosophical roots — and its story begins in ancient times.

It All Begins in Antiquity

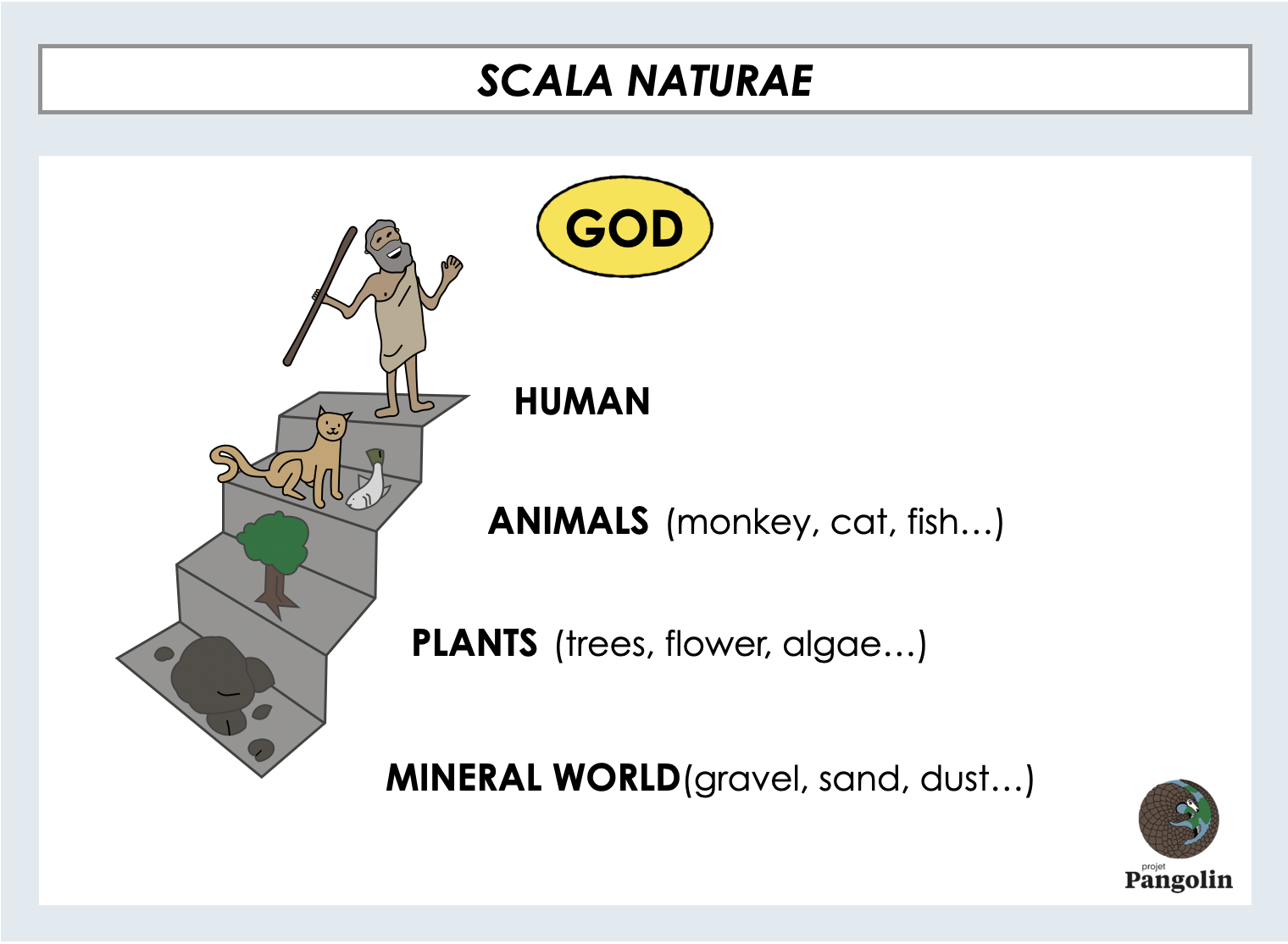

As early as Antiquity, philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle were already pondering the nature and place of living beings in the world. Aristotle even developed an early system of animal classification known as the Scala Naturae — or “Great Chain of Being.”

Aristotle’s idea was based on the belief that living beings could be ranked on a hierarchical scale according to their degree of “perfection.” At the top of this Scala Naturae were the angels, with humans placed just beneath them. All other creatures occupied progressively lower rungs of the ladder [1].

Later on, Aristotle’s thinking became intertwined with Christian theology. In medieval Europe, it was widely believed that each species had been individually created by a divine being. Furthermore, it was thought that species were fixed — unchanging over time.

Over the centuries, however, a growing number of scientists became captivated by the incredible diversity of life. Motivated by curiosity and wonder, they began to describe the natural world in increasing detail.

Natural Selection in the Modern Era

Between 1600 and 1800, the idea that “the path to God lies through the contemplation of His works” became deeply influential. This belief inspired much of the early work in natural history, leading to ambitious efforts to classify the living world. Yet a major challenge persisted: how should life forms be grouped and defined?

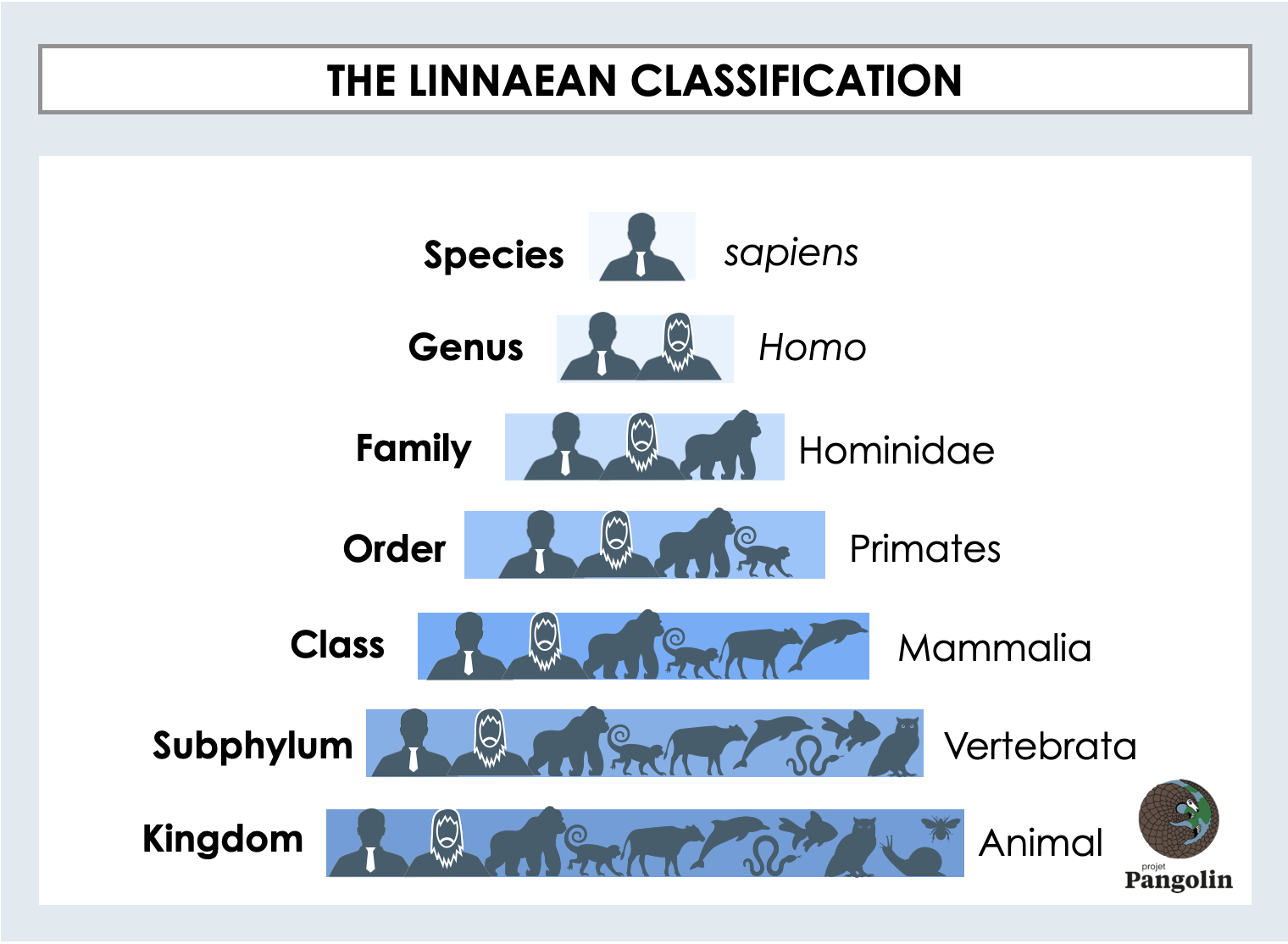

In the 18th century, the Swedish botanist Carl von Linné (Linnaeus) proposed the concept of the species as the basic unit of classification. He introduced a hierarchical system that grouped organisms based on structural similarities: Species, Genus, Family, Order, Class, Phylum, and Kingdom [2].

Linnaeus classified species as if they were fixed and unchanging — in other words, as if evolution didn’t occur. But occasional hybrids between species (a phenomenon well known to dog breeders, for instance) hinted that the boundaries between species might not be as rigid as once believed.

Over time, the discovery of fossilized remains further challenged this static view of the natural world. Fossils introduced the radical notion that species could go extinct [3]. During the Enlightenment, naturalists began to distance themselves from strictly religious interpretations of the natural sciences. A shift in thinking was underway: species might actually change over time!

Lamarck’s Evolutionary Theory

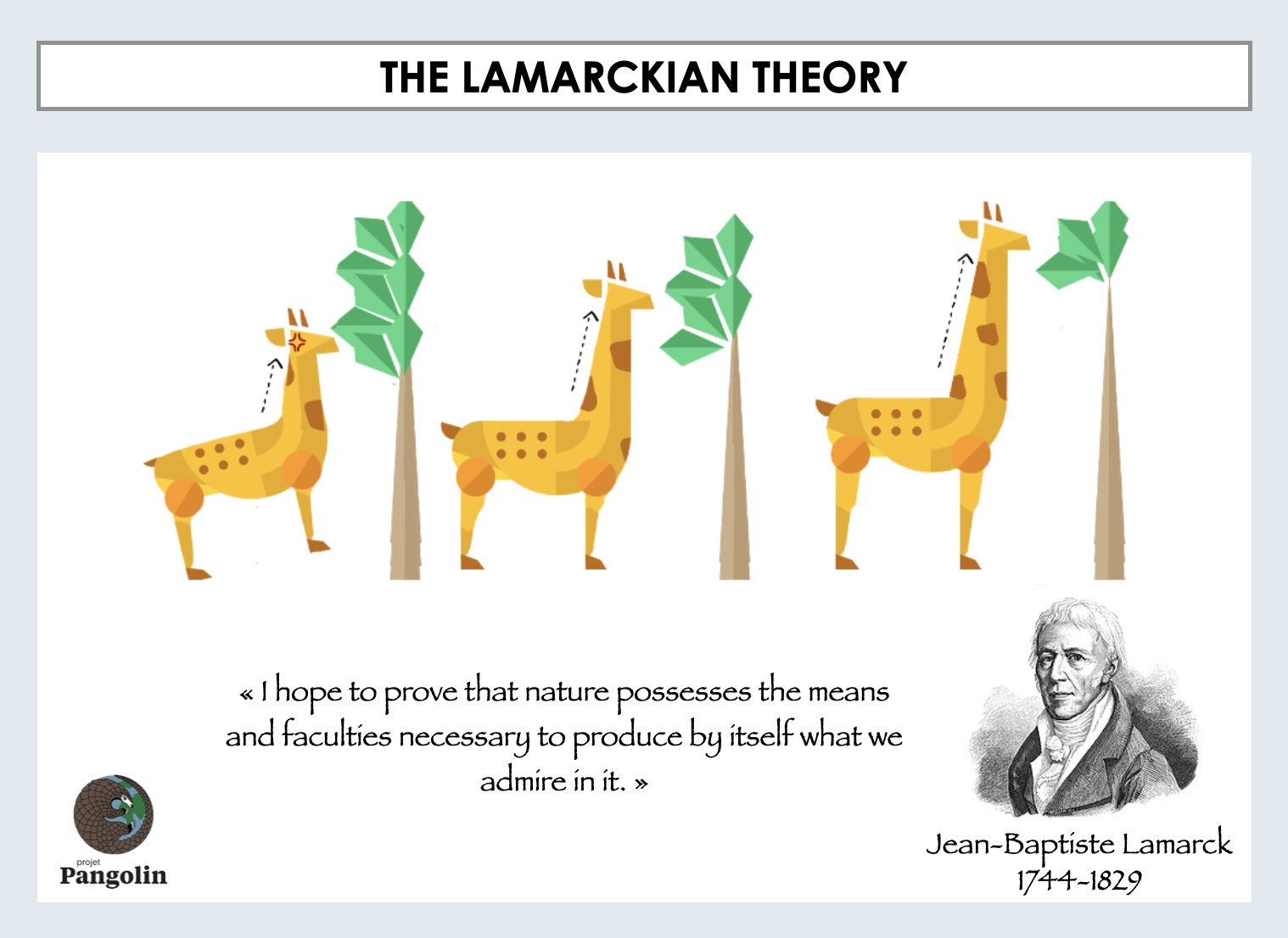

In the early 19th century, French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck was the first to propose a full-fledged theory of organic evolution [4]. His goal was to explain what an animal is — how it forms, how it functions, and how it might change. According to Lamarck, living organisms had the ability to respond — we would now say “adapt” — to changes in their environment. These physical changes were driven by an internal “vital force” and could be passed down from one generation to the next through a process later called the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

To understand this theory, let’s look at a classic example: the long neck of the giraffe. Lamarck proposed that giraffes originally had necks similar in length to those of other animals [1]. But to reach the leaves high in acacia trees, they had to stretch — and stretch — and stretch. Over the course of their lives, this repeated effort gradually lengthened their necks. These changes were then passed on to their offspring, who continued the trend, eventually resulting in the long-necked giraffes we see today.

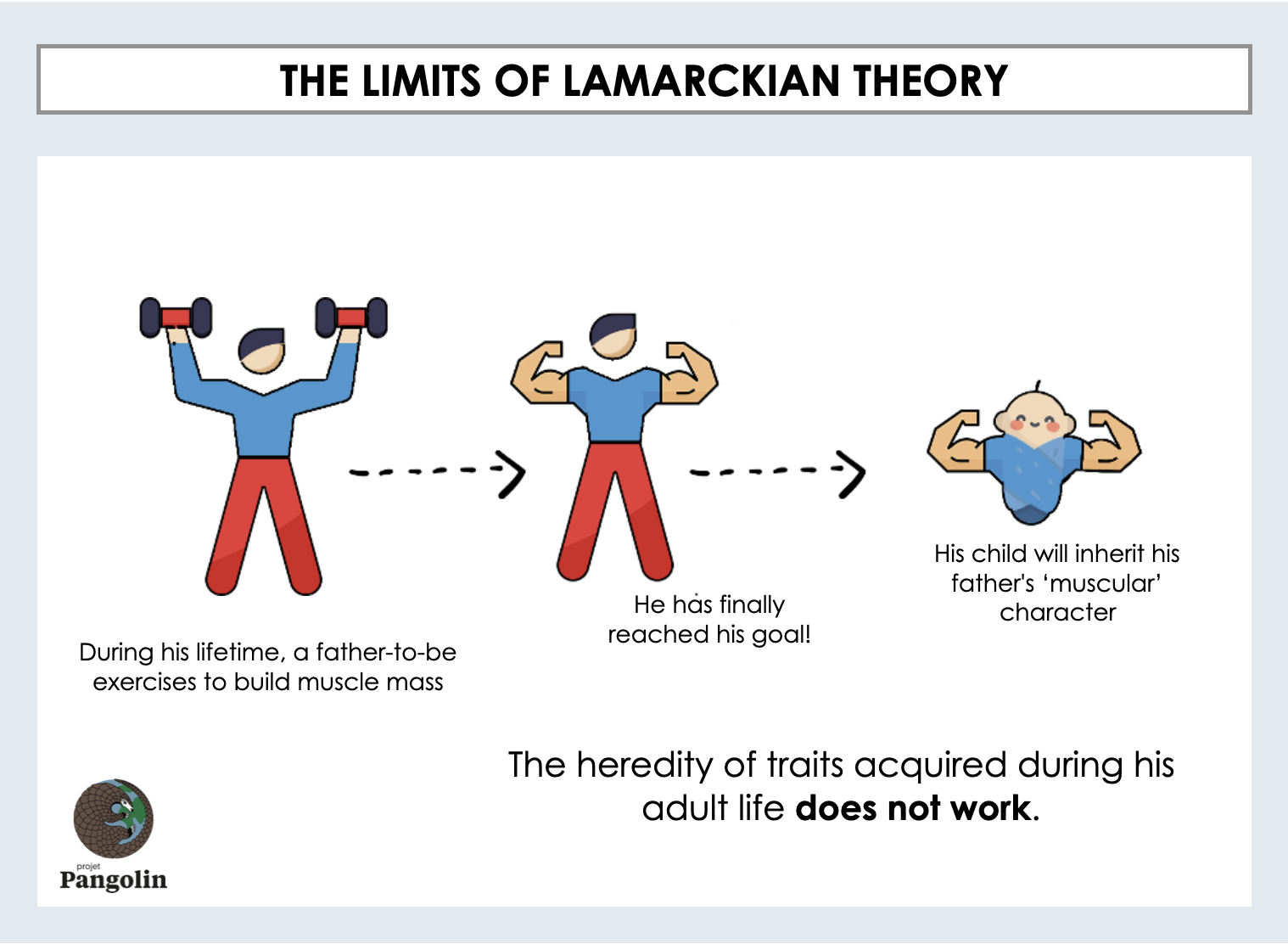

Despite the revolutionary nature of Lamarck’s theory1, the evolutionary mechanisms he proposed — collectively known as transformism — were far from convincing. And you’ve probably already spotted the issue! Just because one of your parents took up bodybuilding before you were conceived doesn’t mean you’re going to inherit all their hard-earned muscles!

What About Epigenetics?

I won’t wade into the current debate around the supposed revival of Lamarckian ideas in light of recent discoveries in epigenetics (i.e., the inheritance of traits not directly encoded in genes). But it’s worth noting that, since the 1990s, solid evidence has accumulated in several species — especially plants, nematodes, and insects — showing that epigenetic inheritance can, in some cases, mimic genetic inheritance, albeit in a less stable manner (see [5,6] for a more detailed discussion and [7] for a critical perspective on the analogy).

Charles and Russell: Evolution’s Headliners

Although evolutionary ideas had circulated for centuries, it wasn’t until the work of Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace that biological evolution gained widespread acceptance [8]. In an era still largely shaped by theological thinking, Darwin and Wallace stood out for their rational, evidence-based approach. Unlike their predecessors, they embraced the reality of scientific observations and sought plausible mechanisms to explain how species change over time.

The boldness of their work lay in the fact that they offered a coherent, natural explanation for evolution — one that didn’t rely on divine creation or static species. This groundbreaking mechanism was called natural selection. Darwin and Wallace concluded that all living organisms are shaped by purely natural processes — not by a deity crafting unchanging species once and for all.

They identified two fundamental challenges faced by all organisms: survival and reproduction [9,10]. To thrive, individuals must not only survive — by feeding efficiently, avoiding predators and pathogens, and enduring environmental stresses — but also reproduce and produce numerous offspring.

The Principle of a Scientific Theory

At this point, it’s important to clarify that a scientific theory — like the theory of evolution by natural selection — is not just a guess or a hunch. It’s a well-substantiated explanation of a natural phenomenon, much like the theory of gravity. It has been tested, refined, and supported by extensive empirical evidence.

Over time, the theory of evolution has itself evolved — enriched by major scientific discoveries, including the field of genetics.

So, How Does Natural Selection Work?

To put it simply: chance proposes, nature disposes!

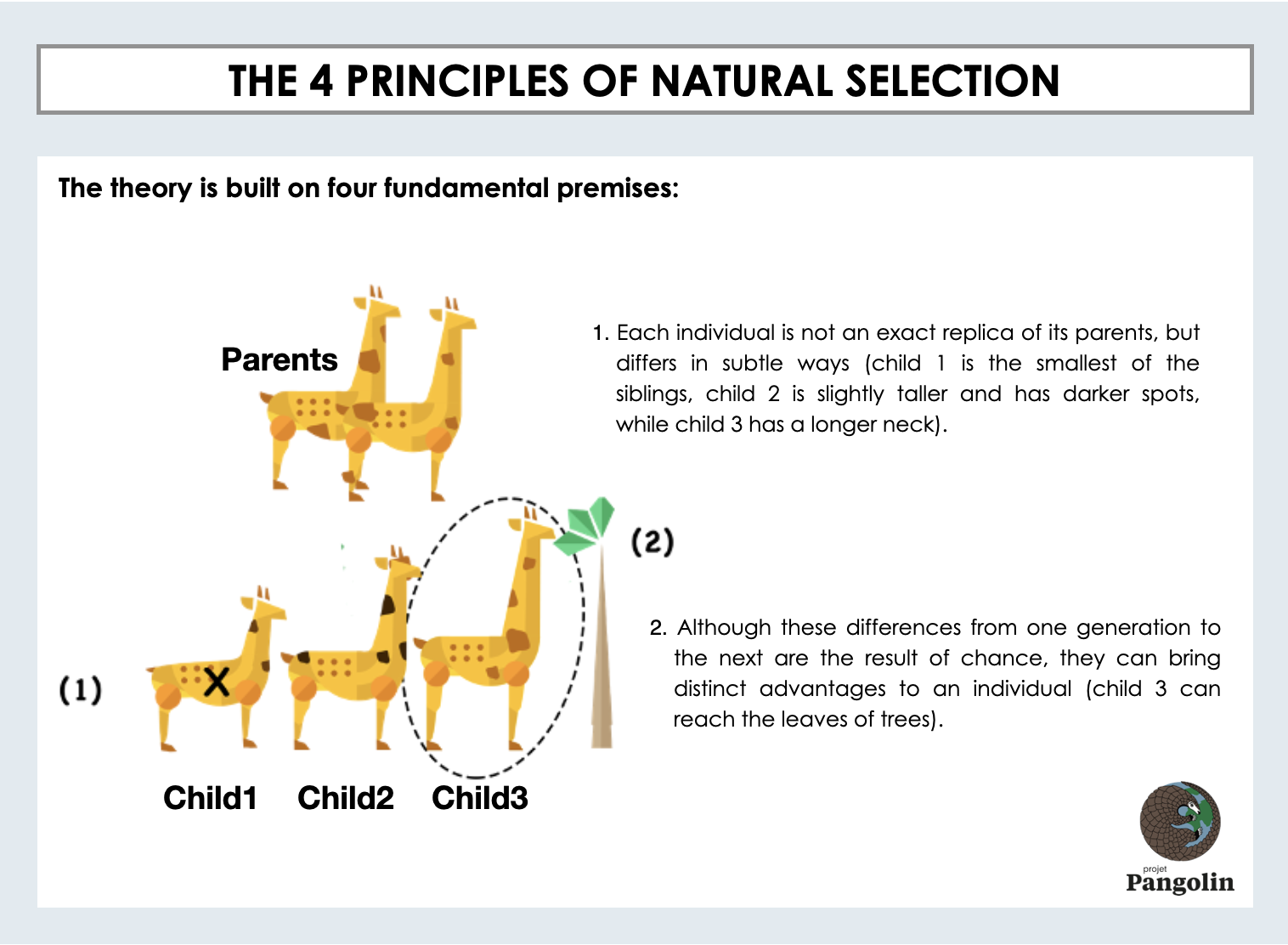

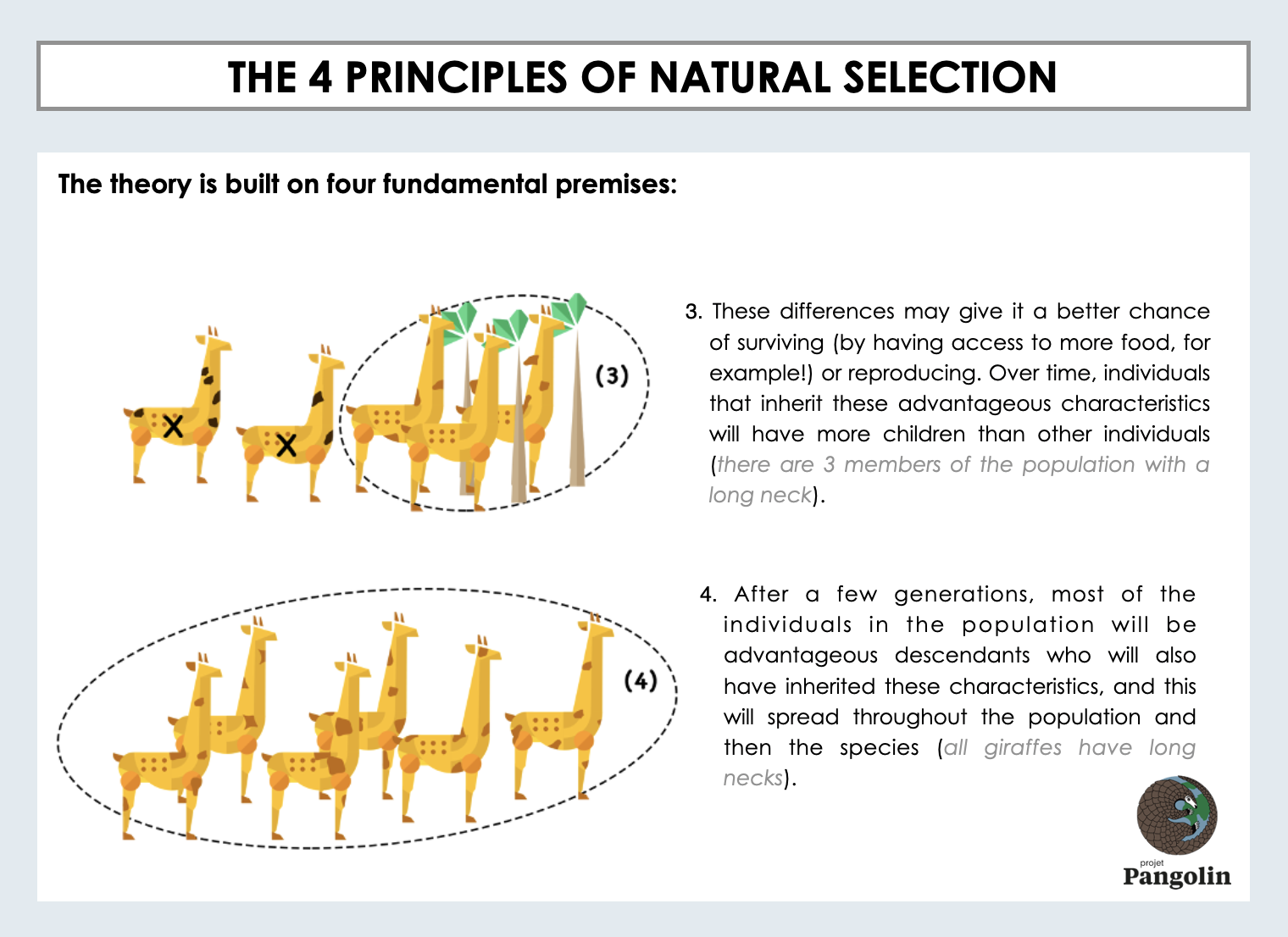

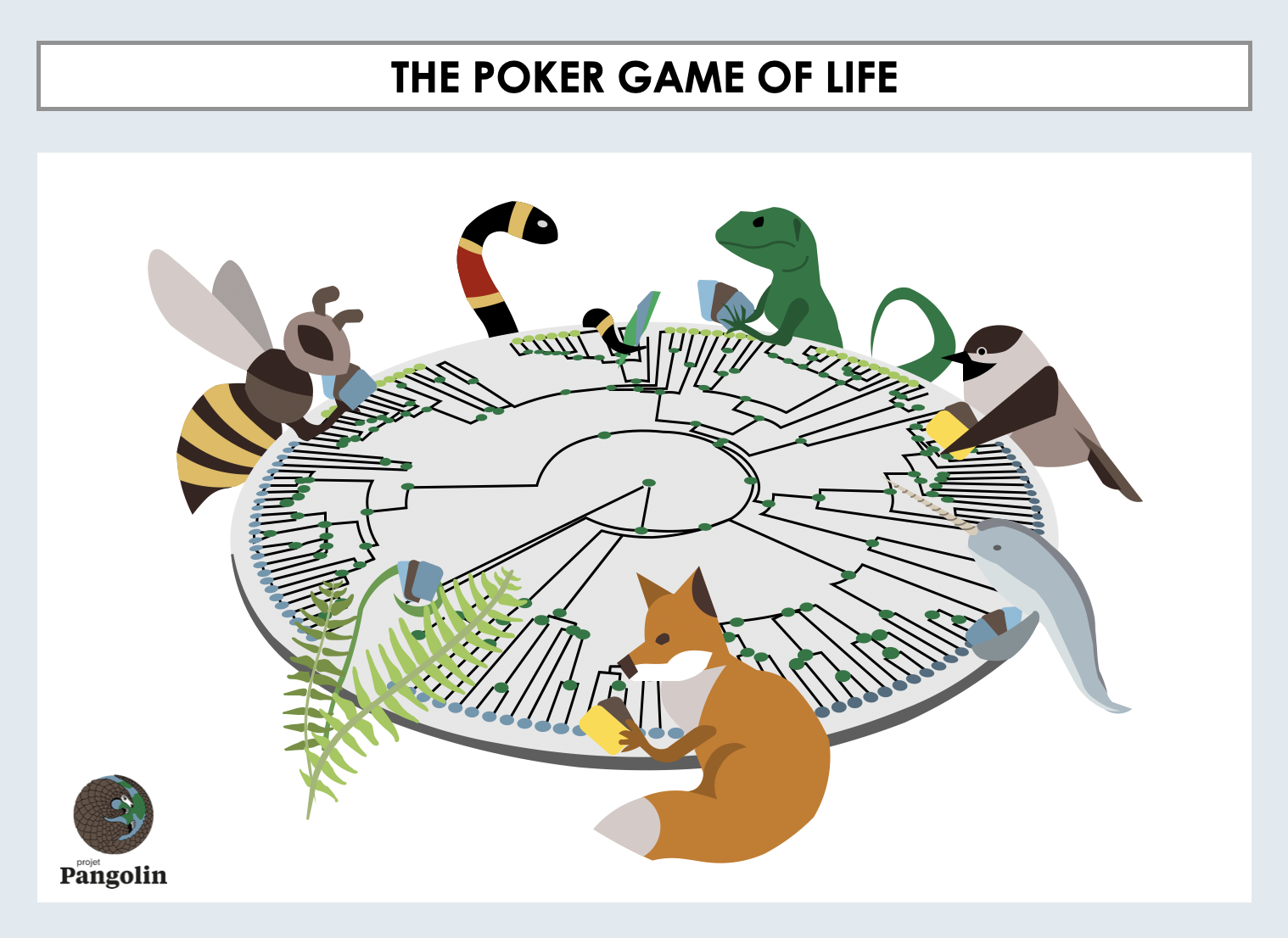

We should understand natural selection as a process without intelligence or intention. It has no goal, no purpose in the grand scheme of things. Simply put: chance deals the cards, and nature plays the hand.

Imagine, for a moment, a round table where all living species are playing a game of poker. Each species is dealt a hand of cards, shuffled randomly. These cards represent the diversity found both between species and within them.

Just like in any card game, the hands are reshuffled with each round. As the game goes on, natural selection favors the most advantageous cards — those traits that provide a benefit in a given environment — ultimately determining the fate of each player at the table.

The players (i.e., the species) don’t get to choose which cards to play to stay in the game. Instead, it’s natural selection, as an evolutionary process, that “selects” the players whose hands give them a better shot at surviving and reproducing.

But Where Do These Differences Between Individuals Come From?

One word: mutations!

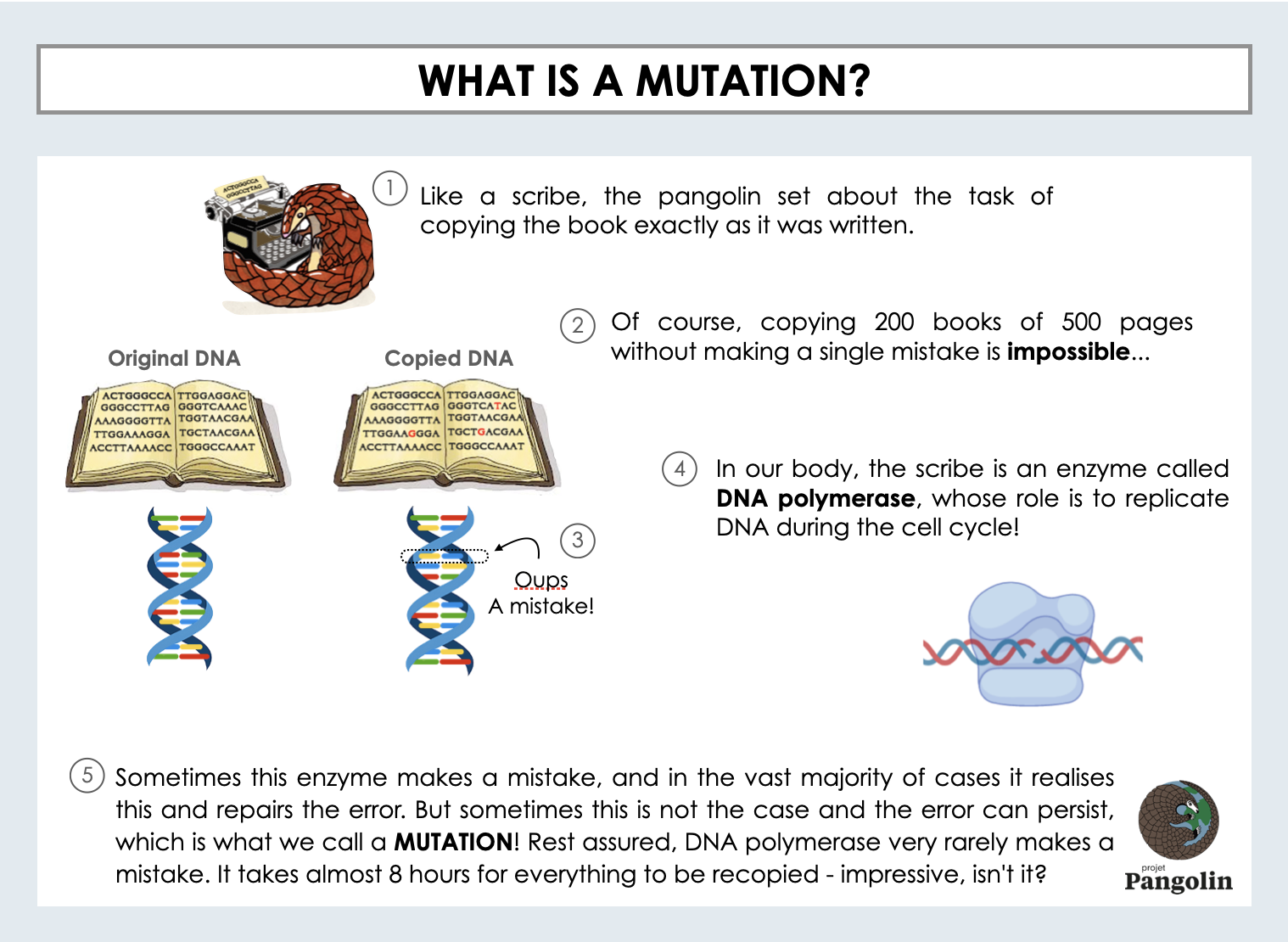

Mutations can indeed be caused by radioactive elements or ultraviolet radiation from the sun — but those aren’t the only sources in nature. In fact, most mutations arise purely by chance, as a result of tiny errors in the cell’s biological machinery [11].

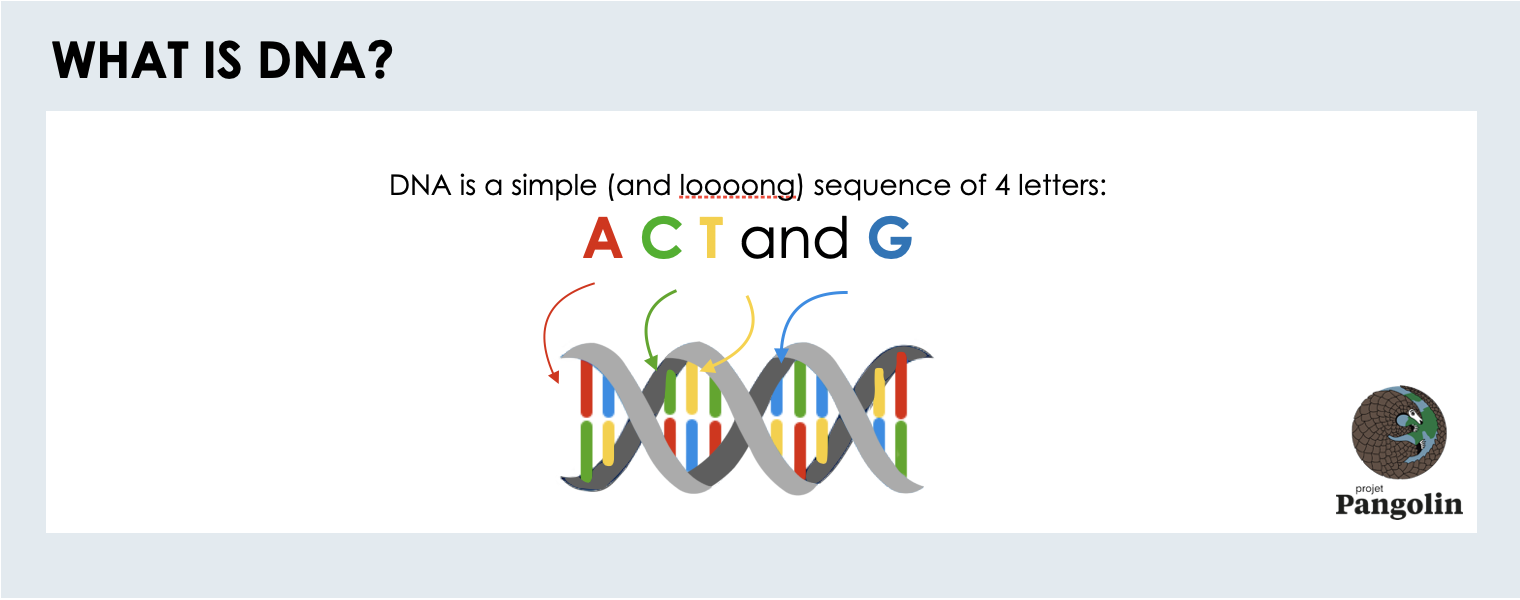

But what kind of errors are we talking about? To understand what a mutation is, we first need to understand what is mutating — and what that means for the species. The answer lies in our genetic blueprint: it’s the DNA that mutates.

In genetics, these “letters” are called nucleotides, and together they make up our entire genome. Our genome contains roughly 6.4 billion nucleotides!

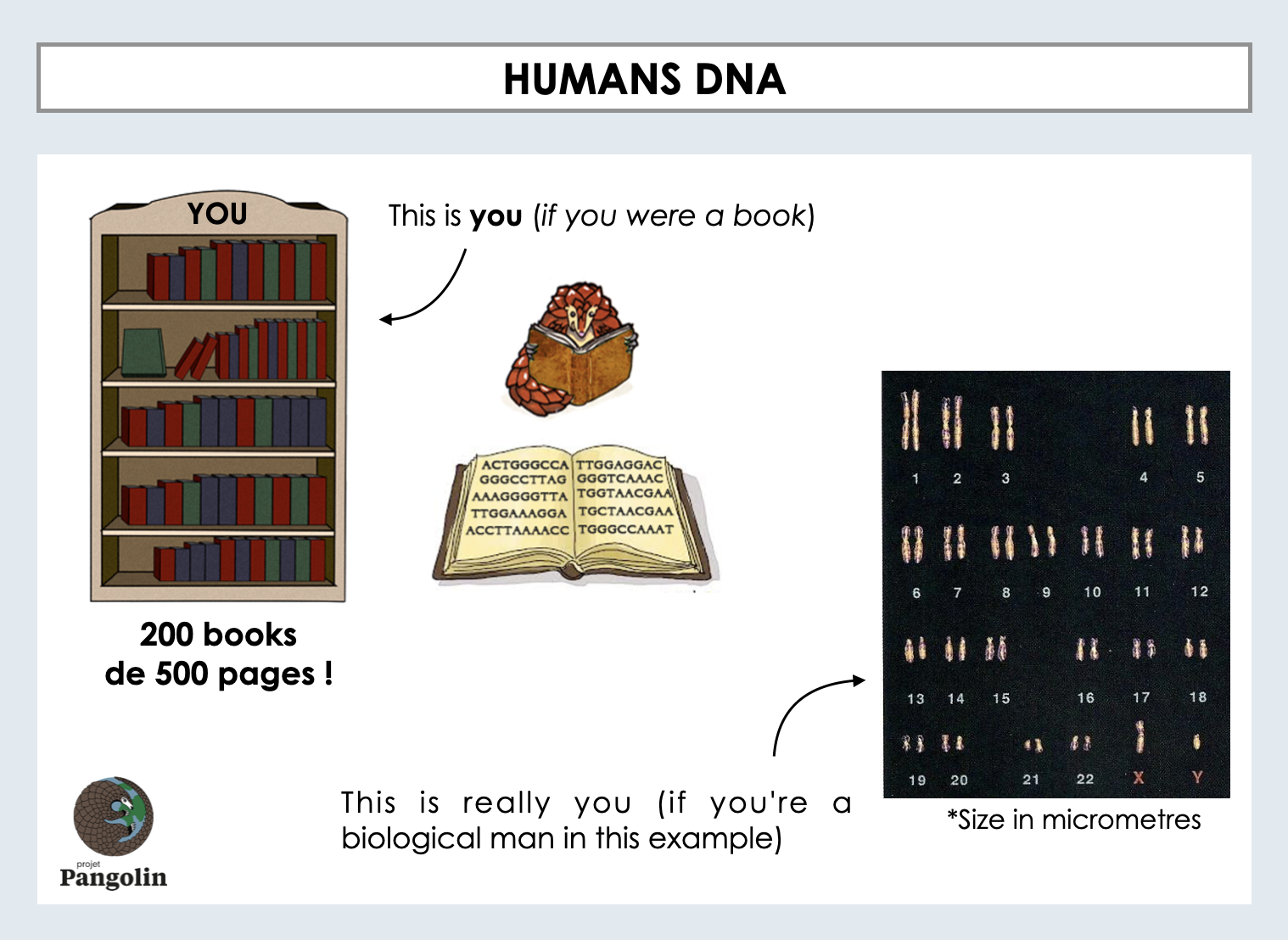

If each nucleotide were a character in a book, our genome alone would fill about 200 books of 500 pages each!

Yet, if we were to unravel all the DNA in our genome and lay it out flat on a table, it would be only about 1.8 millimeters long — incredibly small and incredibly compact.

Among the 6.4 billion nucleotides that make up your genome, half come from your father and the other half from your mother. In a way, your parents passed down these nucleotides to you at conception.

Your DNA is present in every one of your cells — in billions of identical copies. Every second, some cells in your body die while others are created. For new cells to form, your genome must be accurately copied.

In other words, it’s like duplicating those 200 books of 500 pages — and doing it countless times!

You’ve just learned how mutations happen — maybe not as spectacular as the X-Men, I admit! Still, while the cellular machinery that copies our DNA sometimes makes mistakes (about 1 error per 100,000 nucleotides), the vast majority of these errors (99%) [12] are repaired, and most of the rest have no real impact. Only occasionally do these errors change the course of a species’ history — and that’s what we’re about to explore!

But What Exactly Is a Gene?

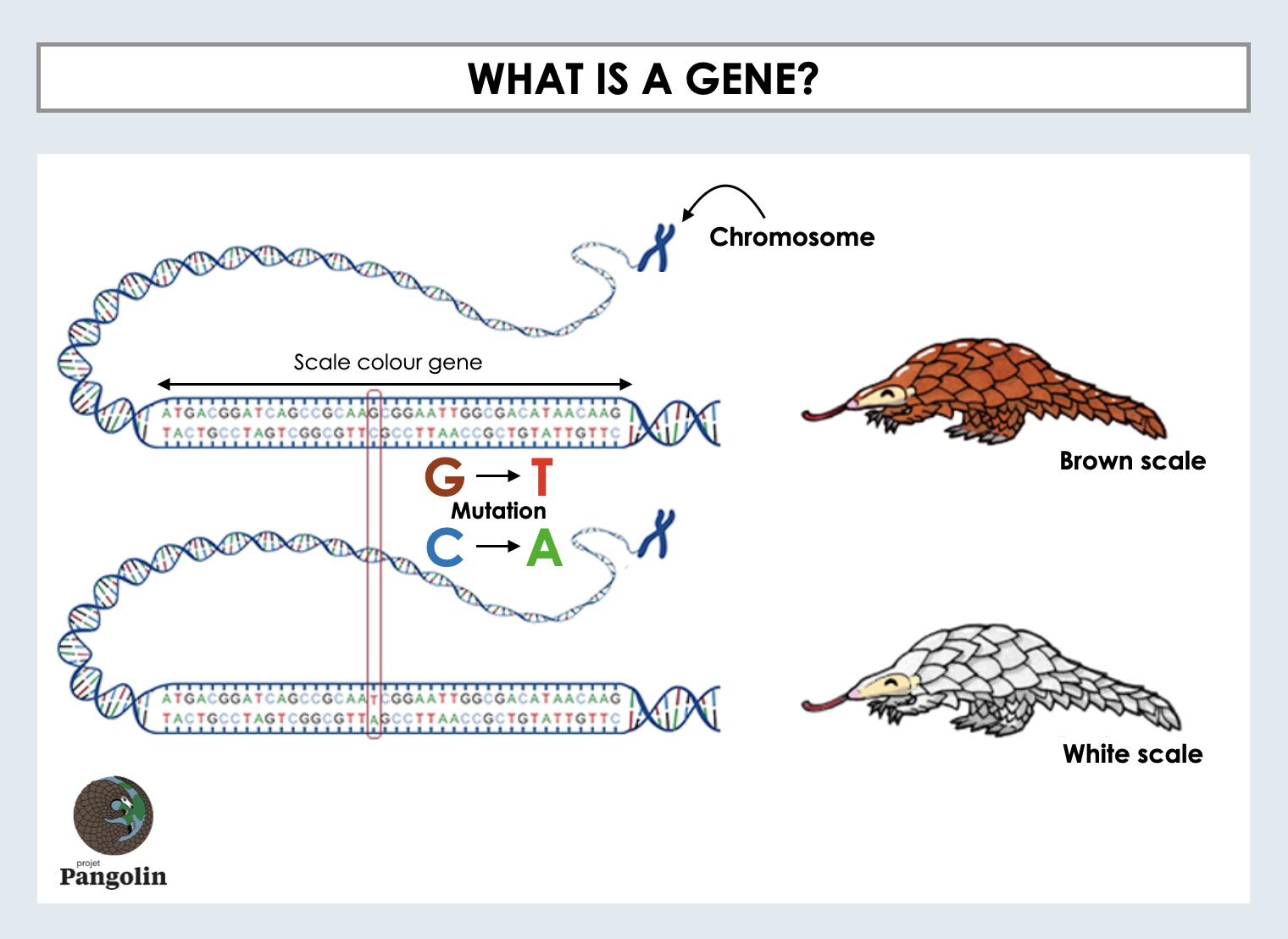

Genes are responsible for the expression of visible traits like eye color, hair color, or the shape of wings, among others. In scientific terms, these traits are called the phenotype.

That said, we still need to understand how a mutation in a particular gene can affect an individual. One way to think about genes is like sentences with specific meanings. Change a single letter in the sentence, and its meaning can change completely!

Let’s look at an example:

“CAT ATE RAT” could mutate to: “BAT ATE RAT”

Here, the animal eating rats changes depending on the version — a small change with a big difference, it is unlikely to see a Bbat eating a rat tho..

Now, let’s imagine a hypothetical gene involved in the scale color of a pangolin:

During DNA replication, a nucleotide was mistakenly changed from a G to a T. This pangolin now passes down this modified gene to its offspring. It turns out this mutation changes the color of its scales, which become white instead of brown!

Now imagine a white pangolin in its natural environment. It would stand out immediately to predators, while a brown pangolin would blend in much more easily. It’s easy to see that, through natural selection, the brown individuals are more likely to survive and reproduce.

Example in Humans

To convince you even more, why not take a look at our own species? You’ve probably noticed that some of your physical traits resemble those of your mother — and others your father. Yet, you are a unique individual with characteristics that belong only to you!

The explanation mainly lies in mutations occurring in the gametes (reproductive cells) of your parents. And, of course, in how you interact with your environment!

On average, a child inherits about 175 mutations different from those of their parents [13]. Among these 175 “letters” might be some that give you an advantage in survival or reproduction in the world you live in — who knows?

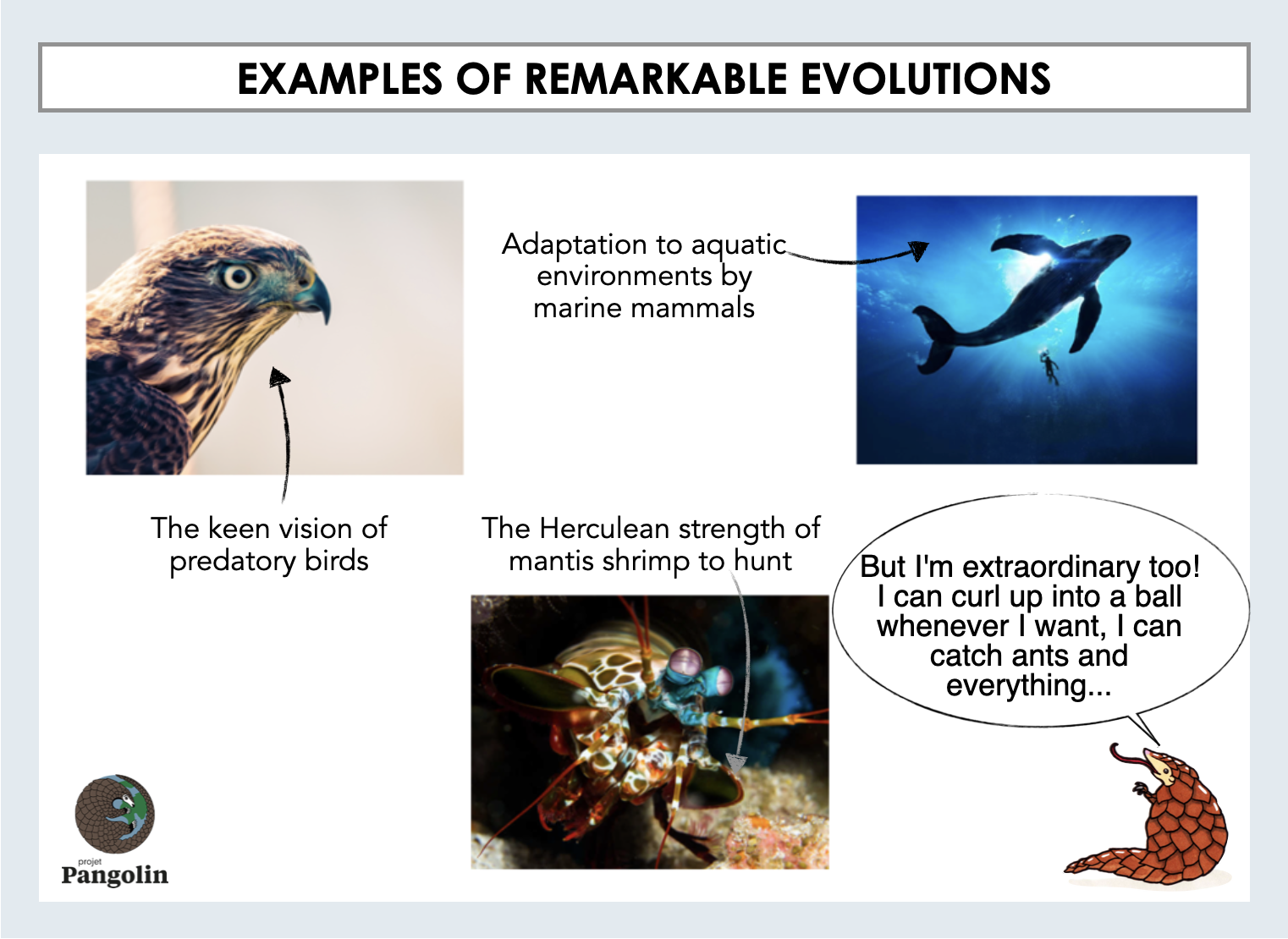

It’s easy to imagine that, after thousands of generations, this process can produce incredible traits:

- The telescopic eyes of a hawk ready to swoop on its prey,

- The incredible strength of a mantis shrimp capable of breaking a skull,

- Or the majestic aquatic ballet of a blue whale —

These are just a few of the countless amazing examples found across our planet.

Natural Selection in Action!

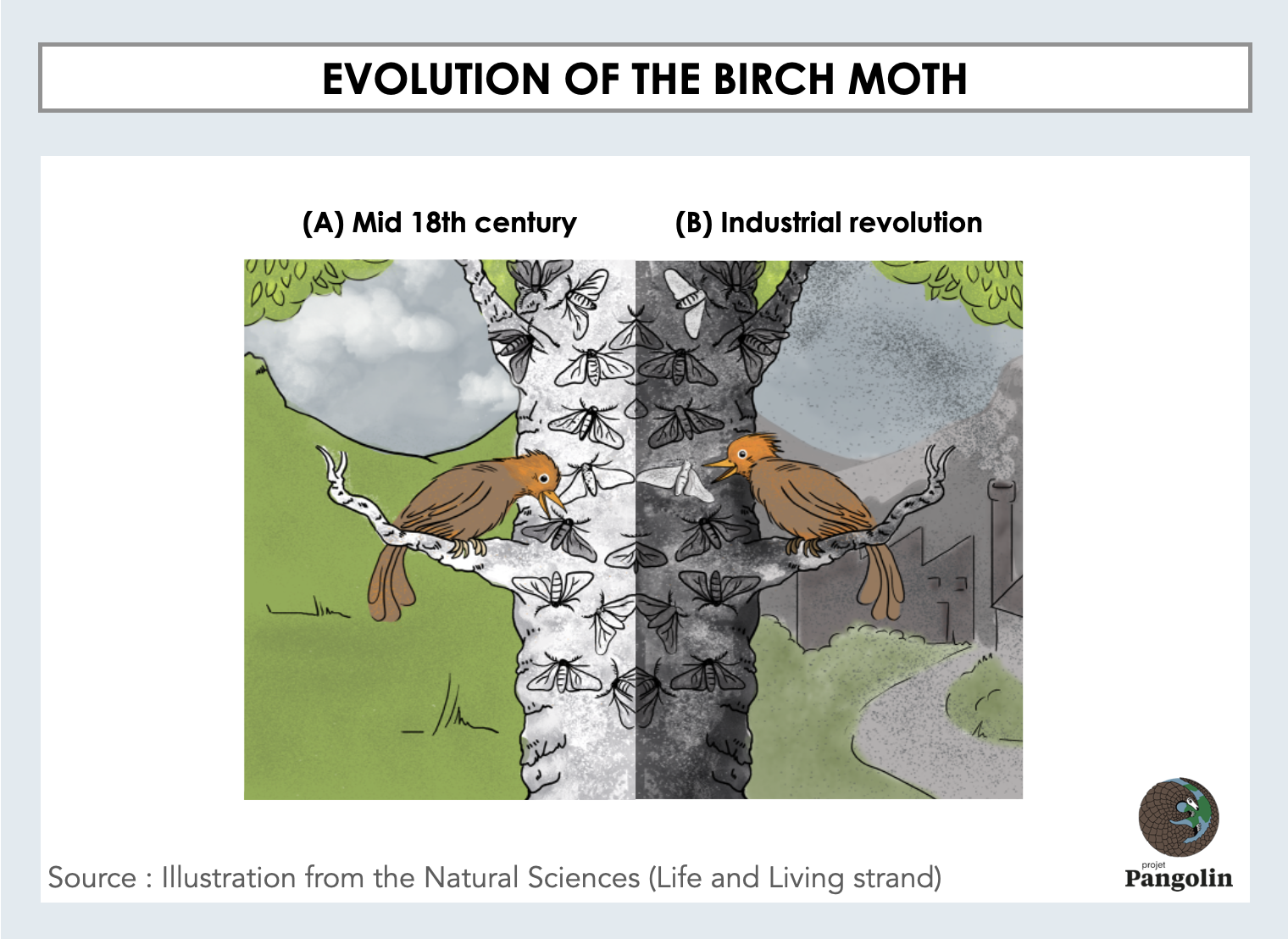

To better understand how a mutation can be favored—or not—in a given environment, let’s look at a well-known example: the peppered moth [14]!

Before the Industrial Revolution

In the mid-18th century, the peppered moth (a nocturnal moth) was mostly pale whitish with small black spots. This coloration allowed it to blend in with the light-colored bark of trees such as birches, providing camouflage from potential predators. Dark-colored moths, due to mutations affecting the genes responsible for wing color, stood out against the pale bark and were thus more easily spotted by predators. These mutant individuals had a lower chance of survival and reproduction.

During the Industrial Revolution

As the Industrial Revolution reached its peak, soot pollution in the air increased dramatically. This caused buildings and trees to darken. Consequently, the lighter-colored moths became more visible to predators like birds, making them more vulnerable to predation. This environmental shift reversed the advantage: dark-colored moths now had a higher chance of survival and reproduction. After just a few generations, black-winged moths became the majority in the population.

Life is in Constant Flux

The example of the peppered moth perfectly illustrates the continuous nature of change. However, evolution is neither a simple process marked only by brief periods of rapid change nor a steady, gradual progression. Instead, it is a complex interplay of random (sometimes sudden) changes, a fluctuating environment, and various forms of competition within and between species.

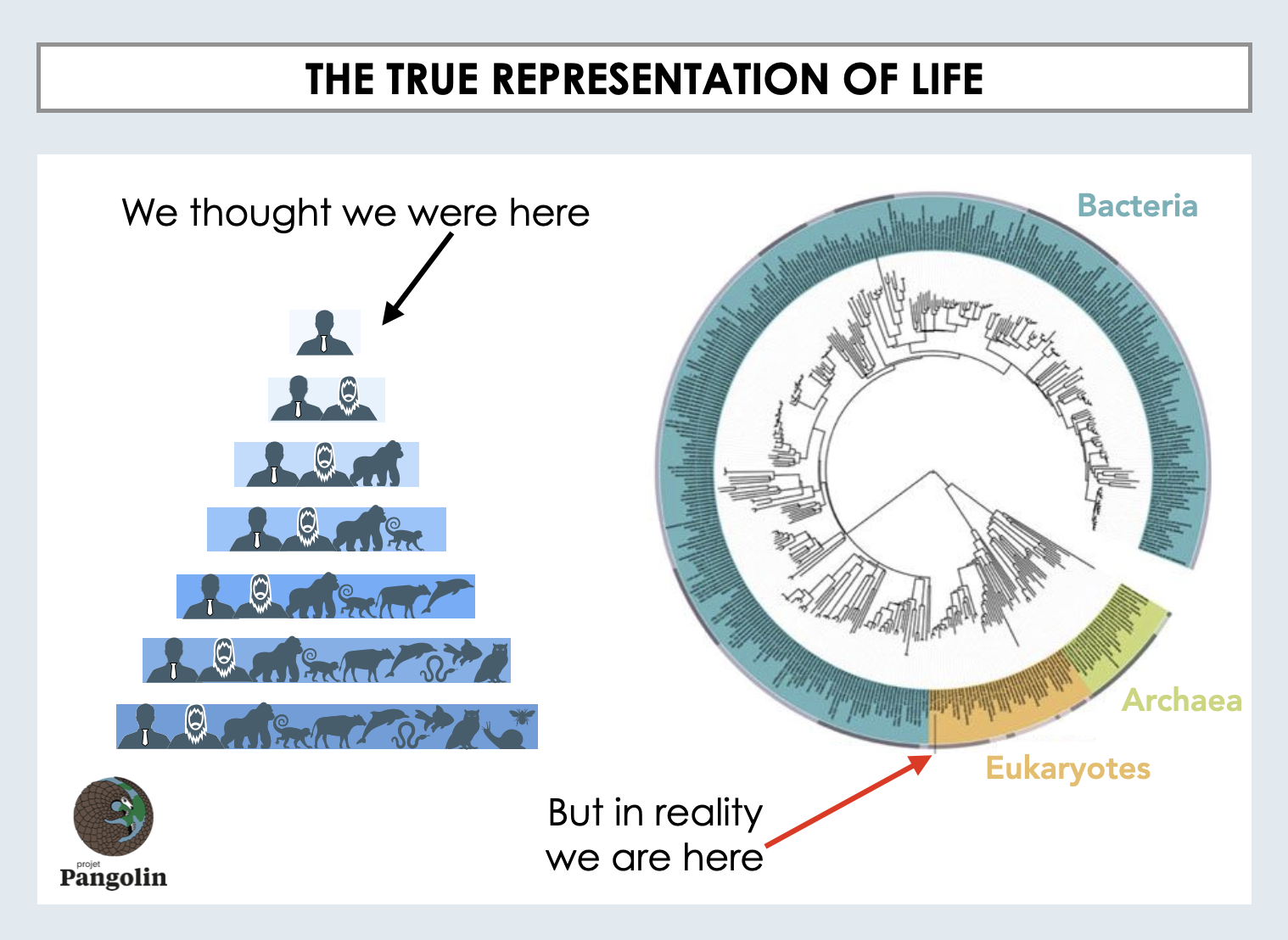

These variables ensure that a species is never fixed in time, accumulating variations over generations. Sometimes people talk about “more complex” or “more evolved” species, but these notions have no meaning in evolutionary biology. All living species today have evolved over the same time span within the tree of life.

To say that a species is “more or less evolved” would imply that some organisms have stopped evolving altogether. Even so-called “living fossils,” like the coelacanth (a marine animal whose fossil form dates back to the Late Cretaceous), only appear stable externally. Stability in form does not mean absence of change—alterations can happen at molecular or other levels invisible to the eye. Change is intrinsic to all life, at every level, and has been since life began.

Controversies Around Natural Selection

The theory of evolution by natural selection has faced two major controversies:

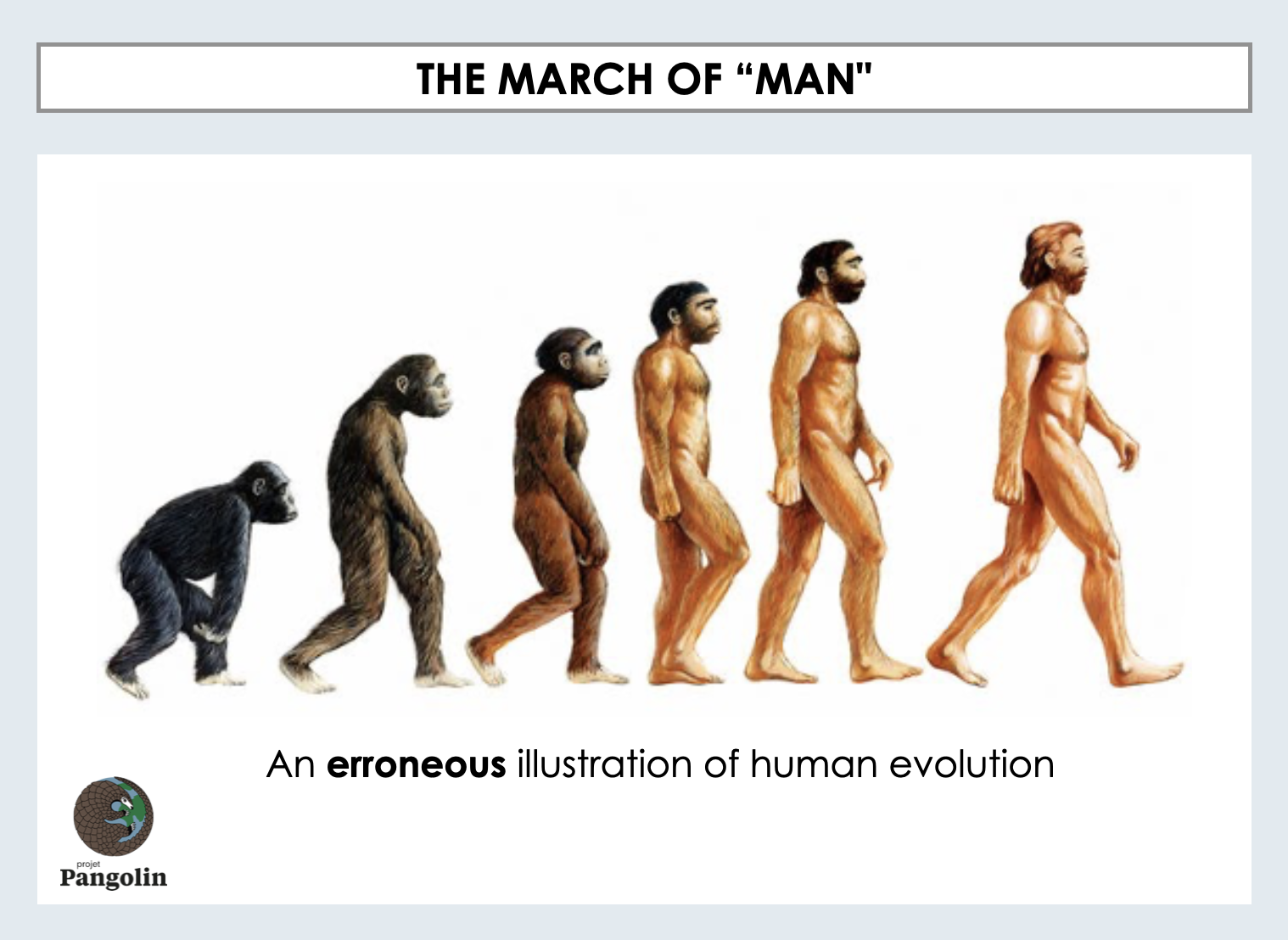

Do humans descend from monkeys?

As Darwinists, we reject the notion of a hierarchy or “ladder of life.” Yet, doesn’t this idea persist in modern depictions?

We’ve all seen the classic image of human evolution: five figures walking in a straight line towards a final goal, Homo sapiens (literally “wise man,” quite the label…).

However, evolution is not directional and does not aim toward any predetermined goal. Humans are therefore not, contrary to what that illustration might suggest, perfect creatures. Every species is constantly evolving. There is no way to measure “progress” in evolution. Thus, the old hierarchical pyramid of life, where humans occupied the pinnacle, has given way to a beautiful egalitarian circle [15], in which every species continues to accumulate variations and evolve!

To sum up, no species is superior to another. If we all share the planet Earth right now—from tiny 3-gram shrimp to majestic African elephants and delicate orchids—it’s because each of us has managed to survive and reproduce.

Rejections of the Theory

Today, the theory of evolution is widely accepted, even by many religious institutions. However, it has often been misused, sometimes twisted to justify actions (including political decisions), or outright denied when convenient for those in power. It’s important to be aware of this. Evolutionary theory is a scientific framework that explains how species change over time on our planet. It helps us understand, for example, why a lion might kill all the cubs in a litter that are not his own. What it does not do is tell us whether such behavior is good or bad. Always be cautious when evolution is invoked in political debates or reform proposals. Sociology exists as a distinct discipline from biology—and for very good reasons.

Final Words

Our body of knowledge is like a glass of water taken from the vast ocean—both insignificant and immense at the same time. Yet, it’s enough to illuminate our minds, or at least mine! You now understand that no species is immutable, not even humans. Each one of us is unique, and it is these differences that natural selection acts upon throughout the evolutionary process.

It’s clear that today, the theory of evolution stands on a broad foundation of evidence from diverse scientific fields. Yet there remains much to discover! We are just beginning to unravel the mechanisms of new evolutionary forces that also have major impacts on the trajectories of species. Among these are migration, random genetic drift, and gene transfer between species. We owe these elegant discoveries to passionate researchers who have succeeded each other over time—and who continue, even now, to unravel one of biology’s greatest mysteries: the evolution of species.

Author: Benjamin Guinet (Reviewed by: Laura Touzot and Salomé Bourg)

Illustrations: Salomé Bourg Reviewing: The Project Pangolin team

References

- Hodos W. (2009) Evolution and the Scala Naturae. In: Binder M.D., Hirokawa N., Windhorst U. (eds) Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-29678-2_3118

-

Gallica.bnf.fr. 2020. Les Sciences Naturelles Au Xviiie Siècle BNF ESSENTIELS. - Fitch, W. and Ayala, F., 1995. Tempo And Mode In Evolution. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

-

Encyclopedia Britannica. 2020. Jean-Baptiste Lamarck French Biologist. - Koonin, E. and Wolf, Y., 2009. Is evolution Darwinian or/and Lamarckian?. Biology Direct, 4(1), p.42.

- Skinner, M., 2015. Environmental Epigenetics and a Unified Theory of the Molecular Aspects of Evolution: A Neo-Lamarckian Concept that Facilitates Neo-Darwinian Evolution. Genome Biology and Evolution, 7(5), pp.1296-1302.

- Loison, L., 2018. Lamarckism and epigenetic inheritance: a clarification. Biology & Philosophy, 33(3-4).

- Ginnobili, S. and Blanco, D., 2017. Wallace’s and Darwin’s natural selection theories. Synthese, 196(3), pp.991-1017.

- Darwin, Charles, 1809-1882. On The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. London :John Murray, 1859.

- Wallace, A., 1870. Contributions To The Theory Of Natural Selection. London: Macmillan.

- J.F. Griffiths, A., 2020. Mutation. [online] Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Pray, L.,2008. DNA Replication and Causes of Mutation. Nature Education 1(1):214

- Asakawa, J., Kodaira, M., Cullings, H., Katayama, H. and Nakamura, N., 2013. The Genetic Risk in Mice from Radiation: An Estimate of the Mutation Induction Rate per Genome. Radiation Research, 179(3), p.293.

- Cook, L. and Saccheri, I., 2012. The peppered moth and industrial melanism: evolution of a natural selection case study. Heredity, 110(3), pp.207-212.

- De Vienne, D., 2016. Lifemap: Exploring the Entire Tree of Life. PLOS Biology, 14(12), p.e2001624.

-

Lamarck paved the way for a new way of thinking. Perhaps God is not, after all, the driving force behind nature. For those who would come after him, this could be seen as a giant leap forward. ↩

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: